🇭🇺 Hungary, 2p | Issued 1930 | Scott C22

Last week, I went to my very first stamp show, Charpex! I met some wonderful artists, exhibitors, and local vendors. I learned the ins and outs of searching through vendor offerings. And I brought home a haul that I was proud of, including old postcards of Asheville (my hometown), new and vintage FDCs, lots of fun mushroom stamps, and some cool overprints.

One stamp in particular I purchased for its cancellation. Nearly perfectly centered on the stamp (albeit upside down), I thought it would be worth researching a little further. But I did not realize it would fly me all the way back to the origins of the Magyar people.

What is the Turul?

America has the bald eagle, and Hungary has the saker falcon. With wingspans between 3–4 feet (up to 126 cm), saker falcons are one of the most distinguished birds of prey in Europe and Asia. The saker falcon can reach speeds of 75–90 mph (120–150 km/h) and has been used in falconry for thousands of years. The species breeds from central Europe eastwards to Manchuria, and winters in Ethiopia, giving it a geographic range commensurate to its size. It has been spotted in Mauritania at the Atlantic to the east and the Yellow Sea off of China to the west, essentially reaching the Pacific. In addition to being the national bird of Hungary, the saker falcon is also the national bird of the United Arab Emirates and Mongolia.

Probably modeled after the saker falcon, Hungary’s Turul is a mythological bird of prey that has become a national symbol of Hungarians. The Turul represents the Hungarian god’s power and will, and it is often represented with its wings deployed and with a flaming sword in its talons. The Turul was seen as the ancestor of Atilla, and it was also the symbol of the Huns.

Why is the Turul a national symbol of Hungary?

In Hungarian tradition, the Turul originated as the clan symbol used in the 9th and 10th centuries by the ruling House of Árpád. The dynasty was named after the Hungarian Grand Prince Árpád, the head of the Hungarian tribal federation during the conquest of the Carpathian Basin, c. 895. Both the first Grand Prince of the Hungarians (Álmos) and the first king of the nation of Hungary (Saint Stephen) were members of the dynasty. The Árpád dynasty ruled Hungary through their national Golden Age until the death of King Andrew III in 1301.

More than just a symbol, the Turul is inextricably linked to the creation and settlement of the Magyar people in their current homeland through three key creation myths.

In the ninth century, the various Magyar tribes that would eventually form the nation of Hungary were pushed from their ancestral lands in the Central Asian steppe by invading forces. It was in this period of transition that Emese, daughter of Prince Önedbelia and wife of Chief Ögyek (Ügek), had a dream. In the dream, she was visited by a great falcon, the Turul bird. The bird told her that from her womb a great river would begin, and flow westward over strange lands. According to her shamen, the dream meant Emese was destined to give birth to a son who would lead his people out of their home, and her descendants would be glorious kings. Emese’s son was named Álmos, meaning “the Dreamt One”, and Emese is credited as “the mother of all ethnic Hungarians”. Álmos was later the father of Árpád.

In a second dream by the leader of the Magyars tribes, eagles (the emblem of the Pechenegs, enemies of the Magyars) attacked the tribe’s horses. It was the Turul who came and defeated the eagles, saving the Magyars.

It is also said that the Turul was sent forth by Isten to personally lead the nomadic Magyars from Central Asia to their new home in the Carpathian Basin. According to legend, in 896 AD, the bird dropped its sword in the great plain along the Danube, indicating to the Magyars that this was to be their homeland. That spot was to become the city of Budapest.

Today, the Turul can be found in the design of coats of arms of the Hungarian Defence Forces, the Counter Terrorism Centre, and the Office of National Security. There remain at least 195 Turul statues in Hungary, and another 50+ in states that were once part of Greater Hungary. This includes one Turul statue with a wingspan of nearly 50 feet (15 meters), which is the largest bird statue in Europe and the largest bronze statue in Central Europe.

Note: In modern times, the Turul has also been associated with a number of fascist and far-right political parties. I hope to cover some of the details of the dark side of nationalism through other stamps in the future.

What are the details of this Turul stamp?

Following the Trianon Peace Treaty in 1918, by which Greater Hungary lost about two-thirds of its territories and population, the Turul also became a strong symbol of “national resurrection.” Unfortunately, this irredentist crusade to reconquer their lost territories drove Hungary to the side of the Axis powers during WWII. However, it was during the intermediate period of nationalist fervor during the late 1920s that this airmail stamp was conceived and released.

In addition to being a symbol of Hungarian nationalism and militarism, the Turul is an obvious symbol for flight and, by extension, aeronautics. The very first Hungarian passenger balloon, which took off on May 1, 1902, was called Turul.

According to the Scott catalogue, there were several stamps overprinted for Hungarian airmail in 1918 and 1920. The first deliberate airmail issue came in April 1924 and featured Icarus soaring in the clouds—perhaps not the most optimistic symbol for a burgeoning airmail industry. Between 1927–1931, Hungary released the Turul issue. Lower denominations featured Turul in a horizontal orientation, wings spread wide in front of the sun. Larger denominations featured Turul carrying a messenger. The messenger is sounding the postal horn with one hand and is holding aloft a letter with the other. The 2p red stamp was released in 1930.

Interestingly, Hungary also considered “Turul” as the denomination for a new currency issued in 1926. Authorities ultimately chose the name “pengő” (equal to 100 fillér), which is the currency featured on this stamp. (The pengő replaced the korona on January 1, 1927, and was itself replaced by the forint after July 31, 1946.)

What does the postmark say?

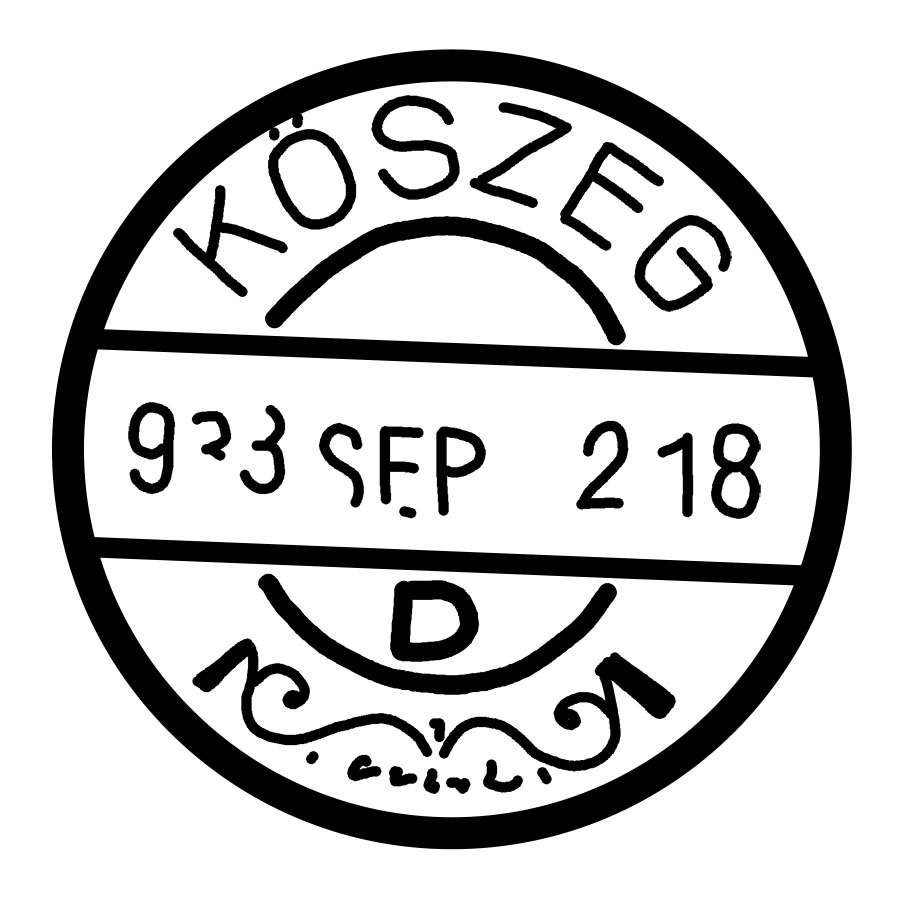

It stands to reason that this stamp was affixed to its original letter upside down because on the loose stamp, the postmark reads upside down. But, oh, what a beautiful postmark it is! This stunningly clear cancellation is perfectly socked on the nose. Though, it does leave me—a beginner—with a couple clear questions, as well.

I’ve recreated the postmark to the best of my ability above. We can clearly see that the cover was sent from Kőszeg, a town in Hungary’s far west that skirts the modern day border with Austria. The town is the site of the Jurisics Castle, built in the 13th century. What was once an active stronghold is now a tourist attraction in a city renowned for its architectural heritage. Every year, Kőszeg hosts Castle Days commemorating and reenacting the 1532 siege by 100,000 Ottoman Turks on the way to Vienna. Outnumbered 100 to one, defenders of the castle (mostly serfs) were able to hold out for 25 days before the Turkish army retreated.

The date line of the cancellation reads “933 SEP 218”. I know that means September 1933, per Hungarian postmark standards. But the day figure confuses me. Was it stamped September 21 or 18? (If it was the 21st, that was the same day György Sándor, Hungarian pianist, was born in Budapest.) My knowledge of postmarks is so far insufficient to understand the significance of the “D” below the date line, as well.

Overall, though, I’m very pleased with this find! A gorgeous stamp, a precise cancellation, and an intro into Hungarian national mythology to boot—This one will be hard to beat.

Other Turul stamps from Hungary

Because of its nationalist-revisionist symbolism, the Turul was tacitly banned from Communist iconography. It would only begin popping back up in popular culture (and political usage) after 1989. However, I did find several stamps prior to 1930 that feature the Turul, as well as some more contemporary ones that allude to him. Unfortunately, I do not yet own them all, but I’ll leave the Scott numbers below for readers who wish to check their own collections.

- 47–62 – “Turul” and the Crown of St Stephen, 1900

- B1–B14 – “Turul” and the Crown of St Stephen, 1900

- 3N1–3N8 – Mythical “Turul”, 1920

The listed stamps below do not depict the Turul, per se. However, they do reflect Hungarians’ passion for falconry and their national bird. The stamp for Hungarian writer Miklós Wesselényi features a large bird feather, which I believe may signify the Turul. That, however, can be research for another post.

- 3348 – Protected Birds, Falco cherrug (saker falcon), 1992

- 3555 – Miklós Wesselényi (writer), 1996

- 3995 – Emblem of Border Guard and Falcon, 2006

- 4237 – Protected Birds, Falco cherrug (saker falcon), 2013

- B168 – White-tailed Sea Eagle and Planes, 1943

The appreciation for falcons must run deep in the blood of the people of the Central Asian steppe. I’ve always found these birds to be beautiful creatures, and I must admit to enjoying the idea of having the Turul as my guardian. But what I’ll take away from this stamp is the newfound knowledge of the Ancient Hungarian pantheon and my destiny to learn more.

What do you think? Are you familiar with other figures in the Hungarian pantheon? Can you help me solve the secrets of the postmark on this stamp? Let me know your thoughts!