🇺🇸 United States | Issued April 1972

Fifty years ago, three men did what barely a handful had done before them: They flew to the moon, landed, had a look around, and brought a few souvenir pebbles home.

In fact, their accomplishment was much more astounding than that. The astronauts of the Apollo 16 mission battled technical glitches and equipment failures at every stage of their harrowing journey, some more consequential than others. And they did it all with good humor and professional dexterity. In the end, their 11 day, 1 hour, 51 minute, and 5 second mission was a success, and the men returned home to well-deserved fanfare and accolades.

Through it all, the Lunar Voyage Cachets company documented each stage of their historic mission, postmarking their cachets in time with Apollo 16’s accomplishments. Here is the progress of the Apollo 16 mission, as documented in this set of five cachets.

Apollo 16 leaves for Descarte Region

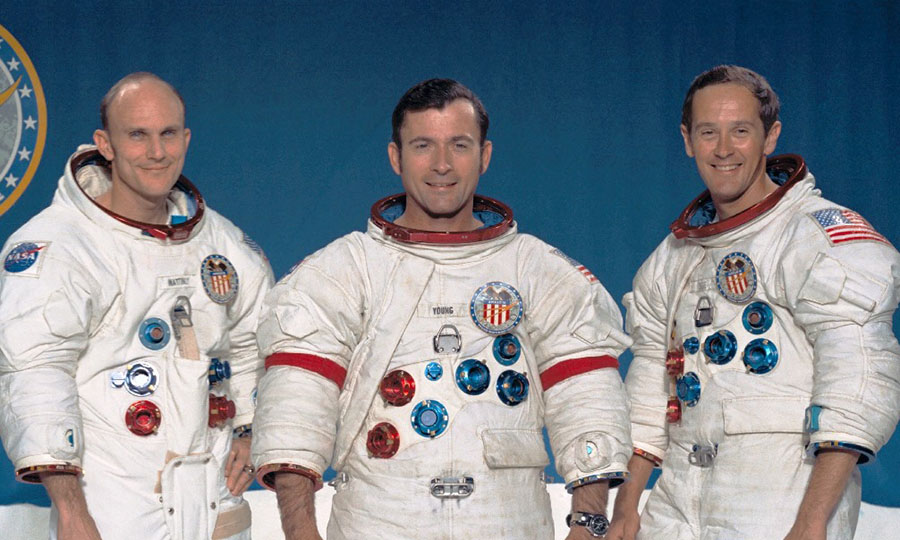

On April 16, 1972, at 12:54 PM local time, Commander John Young, Lunar Module Pilot Charles Duke, and Command Module Pilot Ken Mattingly launched from pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center on America’s fifth and penultimate crewed mission to the moon. They were strapped atop a Saturn V rocket, already 363 feet closer to their target than the personnel on the ground. Their mission: spend three days conducting scientific research. Their destination: the Descartes Region of Earth’s satellite, the Moon.

See the Apollo 16 launch:

Each of the mission’s crew had the experience needed for this mission. Commander Young flew in Gemini 3 with Gus Grissom in 1965, becoming the first American not of the Mercury Seven to fly in space. Apollo 16 was his fourth spaceflight. Mattingly and Duke had known each other for some time as support crew for the Apollo missions. In fact, Mattingly was scheduled to fly Apollo 13, but was pulled from the flight as a precaution after Duke caught rubella from one of his children and exposed Mattingly to the illness. Apollo 16 would be the first spaceflight for both.

Young and Duke explore Descartes area in three rides, obtain rock samples, and activate experiments

In just over four days, the trio crossed nearly a quarter million miles of space with only a few minor technical issues slowing down the mission. Young and Duke undocked their lunar module (LM), dubbed “Orion,” from the command module (CM), “Casper,” 96 hours, 13 minutes, 31 seconds into the mission. Oscillations detected in the Service Propulsion System engine’s backup gimbal system caused a six-hour delay as mission control assessed the risks. They were eventually given the go-ahead. But because of the delay, Young and Duke began their descent to the surface at an altitude higher than that of any previous mission, at 10.9 nautical miles (20.1 km). Orion landed 890 feet (270 m) north and 200 feet (60 m) west of the planned landing site at 104 hours, 29 minutes, and 35 seconds into the mission.

The site chosen for this mission was between two young impact craters, North Ray and South Ray craters, on the Descartes region. The area was chosen because some scientists expected it to have been formed by volcanic action, which would provide evidence of the moon’s makeup and history. (Lunar samples brought back from the mission proved that this was not the case.)

As commander, Young drove the lunar rover during the surface operations, and Duke assisted with navigation. Their first geologic stop for regolith samples was Plum Crater. At the request of Mission Control, Duke retrieved the largest rock returned by an Apollo mission. It was a breccia nicknamed Big Muley after mission geology principal investigator, William R. Muehlberger. During their 71 hours on the lunar surface, Young and Duke collected 211 pounds (95.71 kg) of regolith, took photos, and even engaged in a “Grand Prix” demonstration drive of the lunar rover, which Duke filmed with a 16mm movie camera. (Incidentally, the demo helps prove to skeptics that we’ve actually been to the moon.) In total, Young and Duke traveled 16.6 miles (26.7 km) with the lunar vehicle and spent 20 hours, 14 minutes, and 14 seconds on their three EVAs (extravehicular activities, i.e. moonwalks).

See the Apollo 16 “Grand Prix”:

Aboard CM Casper, Mattingly did not have such a fun time executing his duties. He had a busy schedule operating the various SIM bay instruments for his suite of scientific studies. And that schedule was hampered by a series of mechanical malfunctions, and rushed further by NASA’s decision to bring Apollo 16 home a day early to make up for lost time. However, Mattingly did manage to take a number of photos and operate a variety of scientific instruments during his 126 hours and 64 revolutions alone in lunar orbit.

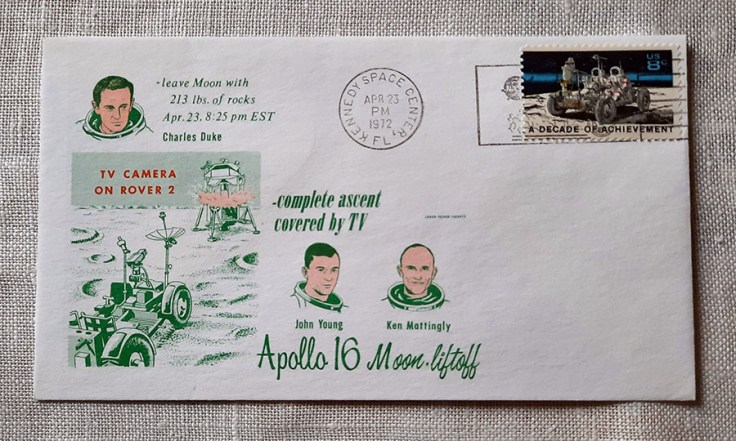

Apollo 16 moon liftoff: complete ascent covered by TV

On April 23, at 8:17 PM EST, LM Orion was cleared for liftoff. Eight minutes later, small explosive charges severed the ascent stage from the descent stage, and the ascent stage blasted away from the moon. The liftoff was captured on camera by the lunar rover, which was not designed to fly back with the crew. Orion captured additional footage of the moon as they sped away from its surface. Within six minutes, the LM was in orbit and eventually made a successful rendezvous with Casper.

See the Apollo 16 moon liftoff TV feed:

Young and Duke worked to move the lunar samples into the command module while minimizing the transfer of lunar dust into the cabin. After that and a series of final checks, the LM was deliberately jettisoned back to the moon. It was supposed to crash intentionally into the lunar surface in order to calibrate the seismometer Young and Duke had left there. But another malfunction fouled up its deorbit, and the LM did not crash to the moon’s surface until the next year.

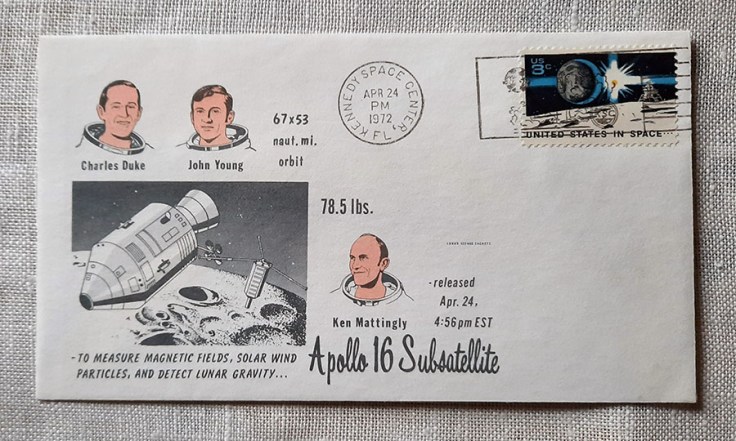

Apollo 16 subsatellite to measure magnetic fields, solar wind particles, and detect lunar gravity

After jettisoning the LM ascent stage, the crew’s next task was to release a subsatellite into lunar orbit from the Command Service Module’s scientific instrument bay. The subsatellite was designed to spend the next year orbiting the moon and taking scientific measurements. Much had been learned in 15 years since the International Geophysical Year about Earth’s composition and atmosphere. But very little was yet known about the moon. However, the subsatellite was launched into a suboptimal orbit and lived for just a month before it, too, crashed to the lunar surface.

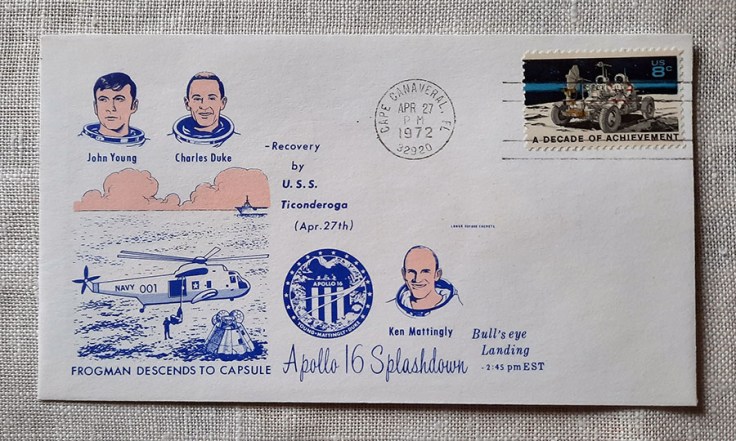

Apollo 16 splashdown: frogman descends to capsule

265 hours, 51 minutes, and 5 seconds after liftoff from Kennedy Space Center, astronauts Young, Mattingly, and Duke returned to their home planet’s surface. They splashed down in the Pacific Ocean 189 nautical miles (350 km) southeast of the island of Kiritimati. Within 37 minutes, they were safely brought aboard the aircraft carrier USS Ticonderoga.

Admiral Henry S. Morgan, Jr. said in his introduction of the Apollo 16 crew, “This is a moment of pride and humble triumph for the crew of Apollo 16. Those of us of the Pacific Recovery Force spread about this ocean are honored to be a small segment of the picture. I know the crew is glad to be back, and we’re glad to see you back.”

See the Apollo 16 splashdown and welcome on the Ticonderoga:

What the covers don’t tell you…

While the Lunar Voyage Cachets cover the scheduled highlights of the mission, there are many notable moments from Apollo 16 that weren’t featured in this series.

In a candid moment while on the lunar surface, Commander Young complained to Duke about the effects of the NASA-prescribed orange juice on his system. Unknown to Young, he had a “hot mike”. “I have the farts, again,” he tells Duke. “I haven’t eaten this much citrus fruit in 20 years!” he adds. “And I’ll tell you one thing, in another 12 f****** days, I ain’t never eating any more.”

Of slightly more historical interest, Mattingly performed a one-hour spacewalk during the crew’s return trip to Earth—the second “deep space” EVA in history. He took his 83-minute EVA to retrieve film cassettes from the exterior of the SM. While he was out there, he also set up a biological experiment, the Microbial Ecology Evaluation Device (MEED), to evaluate the response of microbes to the space environment. Duke remained at the CM’s hatch for the duration of the EVA, offering assistance. As of this writing, Mattingly’s spacewalk remains one of only three deep space EVAs.

Where are they now?

Commander John Young would go on to play critical roles in the U.S. Space Shuttle program. He was critical of NASA’s safety culture following the Challenger disaster, and was assigned to work on safety improvements in the Space Shuttle program. After working at NASA for over 42 years, Young retired on December 31, 2004. He died on January 5, 2018, at his home in Houston and was interred at Arlington National Cemetery on April 30, 2019.

Following his return to Earth, Ken Mattingly served in astronaut managerial positions in the Space Shuttle development program. He would go on to command two space shuttle flights in the 1980s before retiring from NASA in 1985 and from the Navy in 1986. Mattingly moved to the private sector, working in turn for Grumman’s Space Station Support Division, General Dynamics’ Atlas booster program, and as VP of Lockheed Martin’s X-33 development program. He’s currently working at Systems Planning and Analysis in Virginia.

Charlie Duke retired from NASA on January 1, 1976. He entered the Air Force Reserve, rising to the rank of brigadier general before retiring from service in June 1986. Duke was named South Carolina Man of the Year in 1973, inducted into the South Carolina Hall of Fame the same year, and inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame in 1983. Duke currently resides in New Braunfels, Texas, and serves on the board of directors for the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation. He uses his NASA experience and personal stories to inform his role as a popular motivational speaker.

The Apollo 16 command module Casper is currently on display at the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama. It was recently “spruced up” in anticipation of the flight’s 50th anniversary.

What do you think? Do you have other stories about Apollo 16 to share? Do you know of other cachets in this series? Let me know your thoughts!

Leave a comment