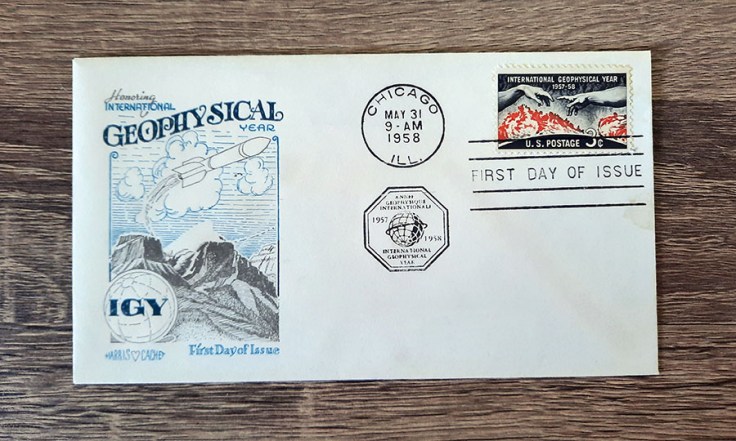

🇺🇸 United States, 3¢ | Issued May 31, 1958 | Scott 1107

When did space exploration begin?

Nailing down an origin point on such a subjective timeline is objectively impossible. Was it with the first human spaceflight in April 1961? Or when the first V-2 rocket crossed the Kármán line in June 1944? Was it with the launch of the first liquid-fueled rocket in 1926? Or the proposal of a “space elevator” in 1895? Or does the origin of space exploration stretch farther back still, beyond Galileo’s first telescopic observations in 1610, beyond Persian mathematician al-Khwarizmi’s astronomical tables in 830, to the first Great Ape to look up to the heavens and reach a grasping hand toward the flickering lights of the night sky?

Well, perhaps that is a little too far back for practical purposes.

When I began thinking about topical collecting, I asked myself a similar question. I wanted my stamp collection to somehow reflect my lifelong interest in cosmology and astronomy. But the 25 lists under the ATA’s “space” category, not to mention the additional dozen-plus lists for astronomical topics and various astronomers, amounted to thousands of items. Even if I were not intimidated by such a number (and I am), I knew I wanted to curate a collection, not amass a jumbled hoard. So, I thought, let’s start at the beginning.

For my personal purposes, I remembered a line that stuck with me from Amy Shira Teitel’s 2016 book Breaking the Chains of Gravity:

The first time President Dwight Eisenhower was presented with the plans, he called the [International Geophysical Year] a unique and striking example of international partners taking advantage of scientific curiosity in a way that promised to benefit nations worldwide.

A peaceful, global scientific effort years conceived of years before the US-Soviet Space Race. An event both my parents lived through but few people know much about today. (It is not expressly mentioned at all in this timeline of space exploration, though four missions within the program are.) Most importantly, an effort whose results had far-reaching scientific and cultural ramifications. And one commemorated in stamps by nations around the globe.

Yes. This would be a good topical focus for me.

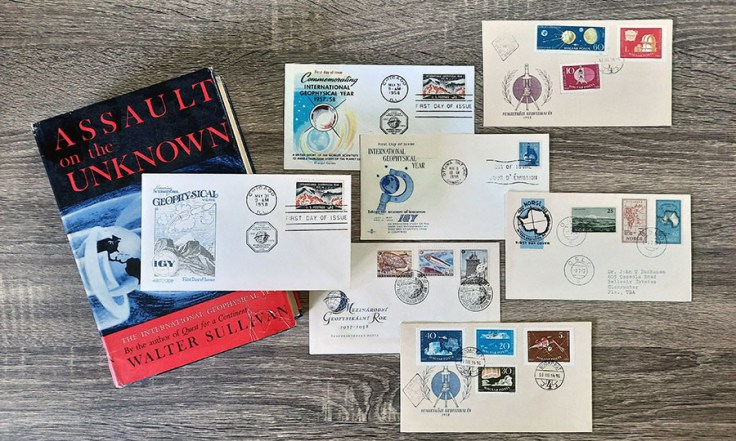

My IGY collection already includes a variety of stamps, covers, books, and memorabilia. Some pieces of rocket mail and numbered souvenir sheets are well worth their own posts. However, to recognize the 65th anniversary of the start of the program this month, I thought it would be best to start at the beginning, with the basics of the program. I hope this introduction is enough to kindle an interest in you, dear reader, to learn more about the International Geophysical Year and all the fascinating science it unearthed.

What was the International Geophysical Year?

The International Geophysical Year (IGY) was an 18-month international scientific effort that encompassed 11 Earth sciences: aurora and airglow, cosmic rays, geomagnetism, gravity, ionospheric physics, longitude and latitude determinations (precision mapping), meteorology, oceanography, seismology, and solar activity. The project ran officially from July 1, 1957–December 31, 1958.

The IGY was inspired in part by the International Polar Years, and was even referred to as the Third IPY. Its timing was chosen in part to coincide with the peak of solar cycle 19, which would aid in many of the solar and atmospheric studies planned for the project.

Which nations participated in the research?

Sixty-seven countries participated in IGY projects domestically and at outposts around the globe. Of the major world powers, China was a notable exception. Though the IGY was structured as a purely scientific endeavor, politics got in the way. The mainland People’s Republic of China protested the participation of the Republic of China (Taiwan) and chose not to send delegates to the program.

Participants included:

Argentina *

Australia

Austria

Belgium *

Bolivia

Brazil

Bulgaria *

Burma

Canada *

Ceylon

Chile *

Colombia *

Cuba

Czechoslovakia *

Denmark

Dominican Republic *

Ecuador *

Egypt

Ethiopia

Finland

France

Germany, East *

Germany, West

Ghana

Greece

Guatemala

Hungary *

Iceland

India

Indonesia *

Iran

Ireland

Israel

Italy

Japan *

Korea, North *

Malaya

Mexico

Mongolia

Morocco

Netherlands

New Zealand

Norway *

Pakistan

Panama

Peru

Philippines

Poland *

Portugal

Rhodesia and Nyasaland

Romania *

South Africa

Soviet Union *

Spain

Sweden

Switzerland

Taiwan *

Thailand

Tunisia

United Kingdom

Kenya

Tanganyika

Uganda

United States *

Uruguay

Venezuela

Vietnam, North

Vietnam, South

Yugoslavia *

As a global scientific endeavor, “the free exchange of data across international borders” was a cornerstone of the IGY. Several World Data Centers were established, each of which would eventually archive a complete set of IGY data and make it available to participating nations. The United States hosted World Data Center “A”; the Soviet Union hosted World Data Center “B”; and World Data Center “C” was subdivided among countries in Western Europe, Australia, and Japan. Today, NOAA hosts seven of the 15 World Data Center locations in the United States.

Which nations issued commemorative stamps for the IGY?

Based on ATA checklist 354 for the International Geophysical Year, 21 nations issued stamps during the IGY (or shortly thereafter) to commemorate their participation (* above). Haiti did not participate, but also issued a popular set of stamps. An additional three territories issued stamps in honor of their ruling nations: Falkland Island Dependencies, French Southern and Antarctic Territories, and Netherlands Antilles.

Since 1960, eight nations and territories have issued commemorative stamps in conjunction with anniversaries of the IGY:

- Bosnia and Herzegovina-Serb

- British Antarctic Territories

- Cuba

- Ecuador

- French So. and Antarctic Terr.

- Greenland

- Hungary

- Peru

What is the legacy of the IGY?

Arguably, the IGY was a cornerstone in the scientific advancements of the 20th century. In my research on the studies and significant achievements of the program, I’ve been consistently amazed by its successes and ongoing legacies.

Among the most newsworthy successes of the IGY were the satellites launched by the U.S. and Soviet Union. Sputnik 1, launched on October 4, 1957, was Earth’s first successful artificial satellite. America’s Project Vanguard rocket and Explorer satellite programs were also part of the IGY. So were the first missions of the Pioneer lunar and interplanetary space probes program.

Explorer 1 also contributed to the discovery of the Van Allen radiation belts. The IGY’s many atmospheric experiments helped us understand for the first time that the Earth’s atmosphere consists of layers, that charged particles from the sun are trapped by our magnetosphere, and that the interaction of the two influences phenomena like auroras, as well as the severity of radiation exposure.

In order to get a true global data set for the atmosphere, stations were set up in the arctic and antarctic. In anticipation of the IGY, Australia established its first permanent Antarctic base at Mawson in 1954. It is now the longest continuously operating station south of the Antarctic Circle. The U.S., Soviet Union, British Royal Society, Japan, France, Belgium, and others also set up research stations on Antarctica. The cooperative effort led to the Antarctic Treaty, signed by 12 nations in Washington, D.C. on December 1, 1959.

IGY sounding research definitively proved that Antarctica is a continent. (Before, we did not know whether and how much land there was under its massive mountains of ice.) Floating research stations on the other end of the globe mapped the bottom of the Arctic Ocean for the first time. And in between, a British–American survey of the Atlantic (carried out from September 1954–July 1959) discovered the full length of the mid-Atlantic ridges. That discovery would help definitively prove the theory of plate tectonics, which was not widely accepted by the scientific community until 1965.

For thousands of years, a person couldn’t dream to reach more than a few hundred feet above his head or below his feet. Then, 65 years ago, the global scientific community coordinated experiments, programs, and other efforts to advance humankind’s understanding of our planet and the space beyond. We were finally able to answer questions about the depths of the oceans, the heights of the sky, our planet’s relationship with our star, and our ability to explore deep space.

And those answers have proven to be only the beginning.

What do you think? How much did you know about the International Geophysical Year? Are you more interested in what the IGY data taught us about Earth or about space? Let me know your thoughts!