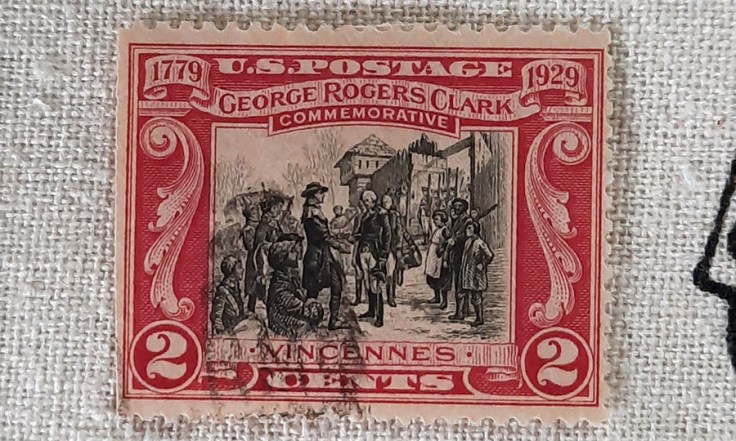

🇺🇸 United States, 2¢ | Issued February 25, 1929 | Scott 651

Picture this: You walk by the break room at work, and you see one. You drive home from work and check your mailbox before going inside, and there one is again. The doorbell rings, and there’s one sitting on your doormat, staring up at you. You deadbolt the door, curl up on the sofa under a thick blanket, and turn on the tube. You see one on TV. You change the channel. And there’s another one!

There’s no escaping them!

In the 20th century, sending and receiving mail were ubiquitous parts of life. So, it’s no wonder that letters, stamps, postal employees, and a variety of jokes at the post office’s expense appeared on television over the years. I’ve been seeing a lot of mail on screen during this Halloween season, including a story about mail that never arrived to its intended recipient.

And what’s spookier than that?

Welcome to the inaugural post in my soon-to-be-ongoing series: Stamps on Screen™.

What was “Eerie, Indiana”?

‘90s kids with playfully macabre natures will surely remember this short-lived show, either from its odd placement on NBC’s primetime lineup, or later syndication on The Disney Channel. “Eerie, Indiana” was about a teenager named Marshall Teller whose family moved from New York City to the strange namesake town. As an outsider, Marshall sees the goings-on in the town for what they are: proof that this outwardly squeaky clean town is actually “the center of weirdness for the entire planet.”

Need proof? Bigfoot eats out of the family’s trash can. Elvis lives on Marshall’s paper route. And notably for today’s post, Marshall and his friend Simon are haunted by the ghost of Spiderman until they serve as interdimensional mail carriers.

What happened in “The Dead Letter”?

Episode 8 of “Eerie, Indiana”’s original 13-episode network run was entitled “The Dead Letter”. In the episode, Marshall and Simon discover an old letter tucked inside a dusty library book. Marshall leaves the letter at the library, but to no avail. As its finder, he begins to be haunted by a young man named Tripp McConnell (played by Tobey Maguire). Trip manipulates the Teller family and even invades Marshall’s dream world in order to convince him to do one thing for him: deliver the letter he was never able to deliver 62 years ago, in 1929.

Marshall and Simon dutifully take the letter to 326 Elizabeth Barrett Browning Boulevard, and what do you know? Mary B. Carter still lives at that address, attended to by her niece. After a few minor shenanigans, Marshall convinces Mary that Tripp was on his way to present her the letter before he was killed by an out-of-control milk truck. (An ongoing menace in the town of Eerie, but that’s a story for another day.) Mary agrees to meet Tripp at the World of Stuff, a popular town hangout that has apparently been operating since at least 1929, and … Well, I won’t spoil the ending for you.

What’s the stamp on the letter?

Over the course of the episode, viewers are treated to several good, albeit quick, shots of the letter in question. We see no return address on the envelope, presumably because Tripp was on his way to deliver the letter in person. But on the upper right side of the cover, there is a two-cent stamp, plain as day: the George Rogers Clark commemorative stamp of 1929.

Issued in February 1929, this stamp would have served the correct first-class one-ounce letter rate at the time. And it would have been readily available by the time Tripp wrote his letter in early November of that year. The two-color stamp features a thick red border with an intricate black vignette. According to the Smithsonian National Postal Museum, “Frederick C. Yohn’s painting ‘Surrender of Fort Sackville’ inspired the stamp’s central design.”

Notably, this was the largest commemorative stamp issued to date (mine measures 39×31 mm), and it was one of only three bicolored stamps issued by the U.S. in the 1920s. Stamp Smarter notes that its “unwieldy” size meant that relatively few were postally used. Nonetheless, it set a record for single day sales from one post office. First Day sales in Vincennes, Indiana (the only location issuing first-day sales) topped 300,000.

🇺🇸 United States, 2¢ | Issued February 25, 1929 | Scott 651

What does the stamp commemorate?

The Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776. By 1779, colonists were heavily engaged in the American Revolutionary War against the British. The late 1920s marked the sesquicentennial of these and other events, and a number of stamps were issued at that time to commemorate key moments during the formation of the United States.

George Rogers Clark (November 19, 1752–February 13, 1818) was a Virginian surveyor, soldier, and militia officer. He became the highest-ranking American patriot military officer on the northwestern frontier during the Revolutionary War. From 1778–79, Lieutenant Colonel Clark led the “Illinois Campaign” to protect Virginia’s interest in the Old Northwest, capturing British forts in the lower Ohio and Mississippi valleys.

When the British retook Fort Sackville in Vincennes, Indiana, “Clark led a desperate march to retake the fort again for the American cause.” Clark’s American troops, aided by French residents of the Illinois country, marched more than 120 miles in 18 days through freezing floodwaters—at times, up to their shoulders—back to the fort. They arrived at Fort Sackville after nightfall on February 23. Though only around 170 men strong, they unfurled flags “sufficient for an army of 500”, giving the British within the fort the impression that their numbers were many times larger. By 10:00 AM on February 25, “the defeated British army marched out of Fort Sackville and laid down their muskets before their victors.”

The recapture of Fort Sackville was a significant one for the Americans. Colonel Clark’s endeavors gave the newly formed United States claim to much of today’s Midwest. In fact, the frontier had an area nearly as large as the original 13 states. With the 1783 Treaty of Paris, America effectively doubled its footprint and gained access to the Mississippi River, a prime trading route. That territory now includes the states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, and the eastern portion of Minnesota.

Today, the exact location of Fort Sackville has been lost. But the George Rogers Clark National Historical Park sits on the banks of the Wabash River in the location believed to be the site of the fort. The interior of the circular granite memorial building features a bronze statue of George Rogers Clark and seven murals by artist Ezra Winter that depict the story and its aftermath.

What do you think? Would you help a ghost deliver a lost letter if you were asked? Is it spooky to think about what would have happened to America if the British maintained control of the frontier? Let me know your thoughts!

🙌🏻 I always respect philatelically accurate propwork! This TV show never crossed my radar but I enjoyed this read a lot.

LikeLike

Thanks! It’s become a tradition to watch a few episodes around Halloween. It’s delightfully spooky.

LikeLike