If you’re familiar with the Butterfly Effect, you’ve heard the metaphor that when a butterfly flaps its wings, it could ultimately cause a tornado on the other side of the earth. The merits of this illustration could be debated in real life execution. But history has seen many localized natural disasters cause mass global effects.

This is the story of the “Year without Summer”, its mark on the Halloween season, and how three very different modern stamps from around the world were influenced by a nineteenth century natural disaster.

What caused the “Year without Summer”?

The year was 1815.

The War of 1812 had just ended in America. On the Continent, Napoleon was returning to France from his banishment in Elba. The first commercial cheese factory opened in Switzerland. And Ceylon became a British colony after the deposition of its last king.

And for one full week in early April, the Earth exploded.

Mount Tambora is a stratovolcano located in what was then called the Dutch East Indies (modern day Indonesia). On April 5, 1815, the volcano blew off its top during an explosive eruption. The mountain ejected one hundred cubic kilometers of ash and debris—enough to bury New York City under 650 feet of ash. The initial blast, ensuing eruption (lasting through April 12), and resulting famine killed an estimated 60,000–117,000 locals. But many more would die over the coming few years.

The Tambora explosion sent thousands of tons of sulfide gas compounds and small particulates into the stratosphere. At this high level of the upper atmosphere, they got stuck, forming a mass the size of Australia that would slowly shift over the ensuing months. This mass of gas and debris reflected sunlight back into space, lessening the amount that would reach the earth’s surface. The result was a widespread cooling around the globe of 2–7 degrees Fahrenheit known as a volcanic winter. It would last more than a year.

Together with a season of heavy rains, June and July 1816 saw heavy snows falling across much of the northern hemisphere. The late snows caused widespread crop failures, which led to a subsequent famine.

1816 came to be known as the “Year without Summer”.

What effects did the eruption have locally and globally?

Though the volcanic eruption was centered in Indonesia, the effects of the blast were felt around the world. And in an era before telegraphy, plate tectonics, meteorology, or atmospheric science, neither news nor an understanding of the eruption and the ensuing climatic changes moved quickly enough to prevent catastrophe. It would not be until the 1970s that scientists would make the connection between the historic blast and its global effects.

According to the U.S. National Park Service, “In July [1816], lakes and rivers remained frozen as far south as northwestern Pennsylvania, while frost remained in Virginia into late August.”

Crops failed across Europe and the U.S. due to the cold or lack of sunshine causing grain and oat prices to soar, torrential rains flooded crops in Ireland, novel strains of cholera killed millions in India, crime became rampant, and people starved in many countries.

Additional hundreds of thousands of people across Europe died of typhus between 1816–1819, precipitated by malnourishment and famine—including 65,000 in Ireland alone. The year 1816 also came to be known as the “Poverty Year” and “Eighteen Hundred and Froze to Death”.

How did the wealthy survive the “Year without Summer”?

While the unexpected volcanic winter and its myriad effects were no doubt difficult for everyone, some fared better than others.

In Geneva, a small group of literary elites sequestered themselves indoors for the unusually cold, wet season. “An almost perpetual rain confines us principally to the house,” wrote Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley from Lake Geneva in a letter dated June 1816. Mary famously spent the summer—if it can be called that—with her new husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley; her stepsister; Lord Byron; and John William Polidori. The group passed the time telling each other stories.

Shelley’s fireside tales would famously become the foundation for her greatest novel, Frankenstein, published in 1818. In the novel, thunderstorms and winter play thematic roles and help set the Gothic mood that has made the story and its iconic monster staples of the Halloween season. Based on similarities in language with letters she wrote that summer, it’s clear that Shelley drew inspiration from the dark and stormy nights at Lake Geneva.

From the same letter mentioned above:

One night we enjoyed [emphasis in text] a finer storm than I had ever beheld. The lake was lit up—the pines on Jura [a nearby mountain range] made visible, and all the scene illuminated for an instant, when a pitchy blackness succeeded, and the thunder came in frightful bursts over our heads, amid the darkness.

And then, from the scene after Victor Frankenstein creates the monster:

I quitted my seat, and walked on, although the darkness and storm increased every minute, and the thunder burst with a terrific crash over my head. It was echoed from Salève, the Juras, and the Alps of Savoy; vivid flashes of lightning dazzled my eyes, illuminating the lake, making it appear like a vast sheet of fire; then for an instant everything seemed of a pitchy darkness, until the storm recovered itself from the preceding flash.

What are the year’s other artistic legacies?

Shelley wasn’t the only creative mind inspired that year. Among the Tambora explosion’s least tragic effects were changes to the art world. The gas and microscopic particles swirling through the Earth’s atmosphere affected the weather and temperature, to be sure. But they also affected the frequencies of light that were able to reach the surface of the globe. According to Smithsonian Magazine, “The particles can’t be seen during the day, but about 15 minutes after sunset, when conditions are right, these aerosols can light up the sky in brilliant ‘afterglows’ of pink, purple, red, or orange.”

James Mallord William Turner was one British artist who took note of the shifting hues in the skies. One of his sketchbooks, simply entitled “Skies” features 65 studies of clouds, sunsets, and moonlight from the post-eruption period. The paint colors he used are considered “vibrant, yet subdued”, and Tate scholars now believe the studies, along with many of his completed paintings, may reflect actual atmospheric conditions he experienced at the time.

Other artists from this period, including German painter Caspar David Friedrich, were also influenced by the resulting vibrant red-orange sunsets. According to Discover Magazine, “in a time before color photographs were invented, these works of art are some of the most accurate depictions of the environmental changes that occurred after the Tambora eruption.”

As an aside, Tambora would not be the first nor the last eruption to influence painters. The colors in Edvard Munch’s famous painting, The Scream (1893), were likely influenced by the devastating Krakatoa eruption of 1883.

What are its philatelic legacies?

In the world of stamp collecting, the Tambora eruption predates the invention of adhesive postage stamps by several decades. But like Shelley and Turner, stamp designers would be influenced by Tambora for many years to come.

Here are three very different stamps from locations around the world that owe their inspiration to Tambora.

🇬🇧 Great Britain, 4½ p | Issued February 19, 1975 | Stanley Gibbons GB 971

In 1975, Great Britain issued a set of four commemorative stamps celebrating the bicentenary of the birth of painter J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851). Turner, as alluded to above, was best known for his “dramatic depictions of sun and sky in landscapes and seascapes”, notably following the “Year without Summer”.

The lowest denomination of this series, seen above, was painted well after the fateful year (in 1841–42) in oil on canvas. The painting was inspired by the death of Turner’s old friend and rival, Sir David Wilkie, who died suddenly off the coast of Gibraltar and was buried at sea. While none of the paintings chosen for the commemorative stamps date to the immediate post-eruption years, each showcases Turner’s use of light and color as “an attempt to express abstract concepts”.

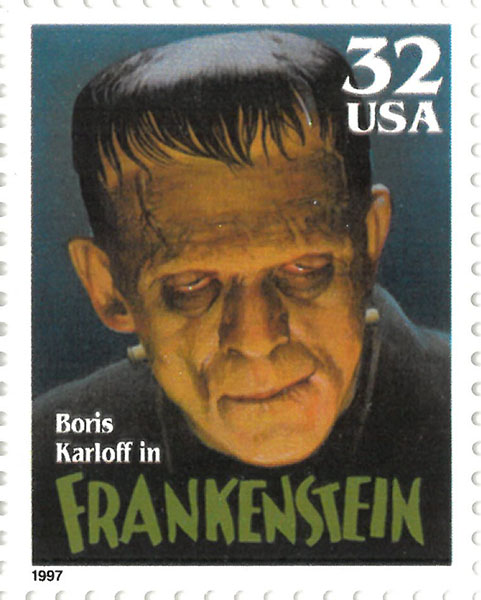

🇺🇸 United States, 32¢ | Issued September 30, 1997 | Scott 3170

This blog has covered the five commemorative stamps honoring the silver screen’s Universal Monsters before. Universal Studios released more than 40 monster films during the period of 1931–1956. In 1931, Boris Karloff starred in “Frankenstein” as the titular mad scientist’s monstrous creation. Universal’s “Frankenstein” is not the most faithful adaptation of the Mary Wollstoncraft Shelley novel—that honor is generally awarded to Kenneth Branagh’s 1994 film. However, Karloff set the bar for how Frankenstein’s monster would be portrayed on screen and in pop culture for the rest of the 20th century and beyond.

Frankenstein’s monster appears alongside the Mummy, the Phantom of the Opera, Dracula, and the Wolf Man in the “Classic Movie Monsters” stamp set. The stamps were designed by Thomas Blackshear II, who also designed several stamps in the American “Black Heritage” series. They were one of the first sets of stamps issued by the U.S. between 1997 and 2004 that were produced with Scrambled Indicia.

🇮🇩 Indonesia, 1,000 Rp | Issued June 5, 2003 | Scott ID 2030

The most recent stamp of the three featured in this post takes collectors back to the scene of the terrible Tambora eruption of 1815. According to IndonesianStamps.com, “Indonesia is a vast equatorial archipelago of 17,000 islands” that stretches east to west from the Indian to the Pacific Oceans. The nation straddles the Pacific “ring of fire”, a tectonic boundary that produces the largest number of active volcanoes in the world.

In 2003, Indonesia issued a set of stamps depicting volcanoes of the Indonesian islands. Ranging from 500–2,000 Rp, the page of 10 stamps and two labels commemorates “50 years of successful ascents of Everest, 29 May 1953”. Two each of five designs feature the volcanoes of Mount Kerinci, Jambi; Mount Krakatau, Lampung; Mount Merapi, Jawa Tengah; Mount Tambora, Nusa Tenggara Barat; and Mount Ruang, Sulawesi Utara. To best depict the shield volcano Tambora and its kin, Indonesia issues the stamps as wide trapezoids, among the few stamps I’ve seen in that shape.

Revisiting the “Year without Summer” this Halloween

As the 21st century grapples with its own climatic shifts and subsequent natural disasters, we would all benefit from remembering how our ancestors dealt with such events.

The “Year without Summer” should be a lesson to us all. Fear of the unknown, fear of the other, and fear of rapid technological and medical advancements dominate the story behind Mary Wolstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein. Around the world, communities separately suffered plague, famine, and floods—though the underlying cause was the same. And artists stepped in where science was not yet able, creating the only records—qualitative though they are—of the volcanic winter of 1816.

In more than 200 years, has the world better prepared itself for the next disaster? Today, more than one million people live within 100 kilometers of Mount Tambora’s still-active peak. Global climate change is causing a variety of natural disasters around the world. Communities are choosing to face each disaster individually after the fact, instead of working collectively to head off further issues. And we continue to see many people decry emerging science and technology as potential solutions, all while opposing the movements of climate refugees through xenophobic rhetoric and legislation.

If there are any arctic ice caves left that are big enough to house Frankenstein’s creation, I’m sure he’s happy to be hiding away. Because two centuries later, we seem determined to keep imposing the effects of “Poverty Year” on each other.

What do you think? Were you familiar with the eruption of Tambora? Did you know the fireside origins of one of our favorite Halloween ghouls? Let me know your thoughts!

Leave a comment