“Freedom and love my creed!

These are the two I need.

For love I’ll freely sacrifice

My earthly spell,

For freedom, I will sacrifice

My love as well.”

―Sándor Petőfi

Two centuries ago, a baby boy born ten miles from the Danube would begin a short but impactful life as a traveling poet of the people, inspiring revolutions at home during his lifetime and around the world for generations to come.

This is the story—and the legendary demise—of Sándor Petőfi, Hungary’s national poet.

Who was Sándor Petőfi?

The hero of our story was born to ethnically Slovak parents on the morning of January 1, 1823 in the Hungarian town of Kiskőrös. The child’s birth certificate, in Latin, listed his name as “Alexander Petrovics”. But as he grew up, the child would voluntarily Magyarize his name to Sándor Petőfi.

Young Sándor and his family would move towns several times, and the child would attend no fewer than eight different schools. However, Sándor had a restless spirit and a taste for theater. He joined a traveling acting troupe against his father’s wishes for several years before leaving to find a more lucrative job. He briefly enlisted as a soldier in the Austro-Hungarian Imperial Army, but was dismissed for ill health (likely from the physical and psychological rigors of active military duty at such a young age). He also worked as a teacher and wrote for a newspaper. All of this before he turned 19.

Sándor stayed with friends for a while in 1842 to get back on his feet after dismissal from the army. In 1844, he used those feet to walk to Pest to find a publisher for his poetry. Under the pseudonym Petőfi, he quickly became a national sensation in the genre of “popular situation songs”. He married a young aspiring poet named Júlia Szendrey in 1847, and the couple bore a son, Zoltán, in December 1848.

How did he come to be Hungary’s national poet?

For a man whose career only spanned a few short years (1842–1849), Sándor Petőfi made an immediate and lasting impact on the Hungarian national psyche.

Petőfi’s early poems drew heavily on the language and elements of Hungarian folklore. Writing poetry in traditional song-like verses was common in the 1840s. And Petőfi’s approachable subjects, unpretentious style, use of vernacular, and clever wordplay helped him quickly gain popularity among the masses—similar to Scotland’s Robert Burns the century before.

However, Petőfi wanted to expand his poetic range, and he soon developed a rich, fresh voice. The Hungarian landscape was a popular subject, and Petőfi’s poetry typified the plains as Hungary’s iconic geographic feature. His later, more mature poems would draw on the themes of death, grief, physical love, memory, loneliness, and—of note—freedom and nationalism. The poet was heavily influenced by the growing populist movement across the continent, and his poetry would continue to skew in that direction.

Sándor Petőfi remains one of the most celebrated figures in the shaping and development of Hungary’s modern national identity. More than just a literary icon, leaders of every political persuasion—and across the political spectrum—have invoked his name to rally supporters. Today, Hungarian children are required to study his poetry and history in school, learning some poems by heart. There are dozens of museums, schools, statues, and streets dedicated to him. “[In] Budapest alone, there are 11 Petőfi streets and 4 Petőfi squares”.

What was Sándor Petőfi’s role in the Hungarian Revolution of 1848?

As a poet of the people, Petőfi easily slipped into the role of the voice behind the Hungarian national revolutionary movement. Based in Pest in the mid-1840s, he and his contemporaries would come to be known as the “Youths of March” (Márciusi Ifjak). The group would gather at the Pilvax coffee palace to promote republican ideals contrary to the Hapsburg aristocracy, and to promote Hungarian as the language of literature and theatre throughout the Kingdom of Hungary.

Early 1848 saw revolutions in Paris (February) and Vienna (March 13). Petőfi “wrote about the French Revolution and compared it to the situation Hungary was in during this period”, “attacking the privileges of the nobles and the monarchy” in print.

Following news from Vienna, Petőfi rushed to Café Pilvax early in the morning of March 15. Around 8:00 AM, Mór Jókai read aloud the 12 points, a list of demands written by the young men who would become the leaders of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. Petőfi recited a new poem for the occasion called “National Song” (Nemzeti dal). The poem inspired the gathering crowd to incite a revolution in the streets, and it remains one of the greatest enduring statements of Hungarian national identity.

The people of Pest and Buda marched throughout the day and into the night, chanting lines from “National Song”. The day-long bloodless mass demonstrations throughout the metropolis forced the Imperial governor to accept all 12 of their demands (thereafter called the March Laws). Changes came quickly, and within about a week, a new Hungarian parliament was created with Lajos Batthyány installed as its first Prime Minister.

What happened to Sándor Petőfi?

Despite initial support, Hungary’s new government was unstable. Batthyány, committed to the ideals of a constitutional monarchy, found himself wedged between the visions of the Austrian monarchy and the Hungarian separatists. By late summer, everyone could hear the rumbles of a civil war.

Petőfi joined the Hungarian Revolutionary Army and served on the Transylvanian front under the Polish Liberal General Józef Bem. Bem recognized Petőfi as a valuable national figure (and may have been aware of his past dismissal from service). So, it’s unlikely that the poet ever engaged in direct combat. Many sources suggest he served mainly as the general’s aide-de-camp and translator (Bem did not speak Hungarian).

In any case, Bem’s army was initially successful against Habsburg troops. However, after Tsar Nicholas I of Russia intervened to support the Habsburgs by sending his own Imperial army—triple the size of the Hungarian troops—the revolutionaries were defeated.

“True to his work, Petőfi died in the struggle for Hungary’s freedom.”

Petőfi was last seen alive around 6:00 PM on July 31, 1849 during the Battle of Segesvár at Fehéregyháza (in today’s Romania). He is believed to have been killed in action (a Russian military doctor’s diary corroborates this), but his body was never recovered. The date of his disappearance is considered to be the date of his death.

Over the years, the legend of Petőfi would continue to grow, and rumors of his survival persisted. His friend Mór Jókai imagined his “resurrection” in an autobiographical novel, Political Fashions (Politikai divatok, 1862) Fake Petőfis presented themselves at country estates throughout the 1850s—most of whom were spies of the Austrian police. His was also a popular specter summoned during the Spiritualist seances of the late nineteenth century.

As late as the 1980s, Soviet investigators found archives detailing Hungarian prisoners of war from the Battle of Segesvár who were marched to Siberia. The records again resurrected rumors of Petőfi’s fate. But alas, these claims were discredited, and Sándor Petőfi’s body has never been found.

His disappearance inspired a Hungarian saying: “Eltűnt, mint Petőfi a ködben” (Disappeared, like Petőfi in the fog).

How did Hungary celebrate the 200th anniversary of his birth?

It was the novelist József Eötvös who in 1847 first stressed that Petőfi is “above all, Hungarian; even his most trifling work bears the stamp of nationhood, and that is why not only his words but the feelings they express are understood by every Hungarian”. Following this line of thought, in his later cult Petőfi was raised up not only as the pre-eminent national poet, but also the proper embodiment of everything Hungarian (mentality, landscape, poetic form), that is, the manifestation of the Hungarian spirit itself. After choosing to be a Hungarian, Petőfi grew to be the incarnation of Hungarian-ness.

(ERNiE)

To fully celebrate such a man born on New Year’s morning, one must begin the year before. According to one source, Hungary dedicated both 2022 and 2023 to the bicentenary of the poet, allocating a full 9 billion HUF to the celebrations. In addition to a stamp issue (see below), Hungary hosted events in more than 200 locations all across the Carpathian Basin. Funds also went to developing museums and regional memorial houses, and renovating memorials. The government financed a series of literary and artistic projects, including book publications; a comic book adaptation of Petőfi’s work, The Apostle; and an operatic adaptation of The Local Hammer.

A major motion picture about Petőfi is currently in production. The film recounts the events of March 15, 1848 during the 24 hours of Revolution Day from the perspective of Petőfi, his friends, and fellow young radicals. The movie is titled “Most vagy soha!”, or “Now or Never!” It is on track to be one of the highest funded films in Hungarian history. The film has a scheduled release date of March 14, 2024.

How has Sándor Petőfi been celebrated in stamps?

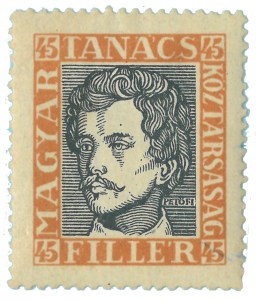

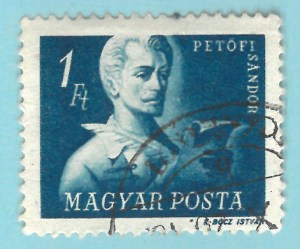

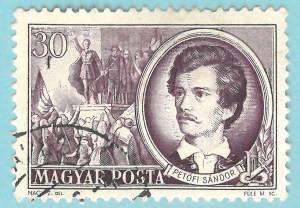

“Both in conservative and (equally nationalistic) Marxist-communist literary histories, Petőfi was celebrated as the ultimate synthesis of genuine folk poetry and high art,” says the Encyclopedia of Romantic Nationalism in Europe. Perhaps then, it is appropriate that he has been featured in so many Hungarian stamps. Postage stamps, after all, also straddle the line between plebeian utility and fine art.

A quick search on Colnect.com brings up 59 stamps, souvenir sheets, and variations dedicated to Petőfi. Most have been issued by Hungary, of course, but Petőfi stamps also grace the catalogs of Romania, the Soviet Union, and most recently (for the 200th anniversary) Serbia.

As a beginning collector, I certainly don’t have a full set of Petőfi stamps. However, among the Petőfi stamps in my collection are:

🇭🇺 Hungary, 45f | Issued June 12, 1919 | Scott HU 199

🇭🇺 Hungary, 10k–50k | Issued January 23, 1923 | Scott HU B72–B76

🇭🇺 Hungary, 1 Ft | Issued March 15, 1947 | Scott HU 823

🇭🇺 Hungary, 40f–1 Ft | Issued July 31, 1949 | Scott HU 848–850, 867–869

🇭🇺 Hungary, 10f | Issued October 16, 1948 | Scott HU CB9

🇭🇺 Hungary, 30f | Issued March 15, 1952 | Scott HU 991

🇭🇺 Hungary, 1–3 Ft| Issued December 30, 1972 | Scott HU 2206–2208

🇭🇺 Hungary, 580+150 Ft | Issued March 4, 2022 | Scott HU 4625

Short of speaking with him in a seance, we will never know what Petőfi thinks of his legend and legacy. But it’s safe to say that his poetry and his life’s story will inspire many people around the world for additional centuries to come.

What do you think? Were you familiar with Sándor Petőfi as a poet or subject of Hungarian stamps? Do you enjoy his Romantic poetry? Let me know your thoughts!

Leave a comment