America is once again rampant with eclipse fever! The April 8, 2024 total solar eclipse will be drawing millions of eyes toward the sky.

I won’t be as close to the path of totality as I was for the Great American Eclipse of 2017. (I’ll just see 86% coverage.) But I, too, have dusted off my specialty eclipse glasses and am ready to view one of the most spectacular sights in the heavens—when the sun goes dark in the middle of the day.

Many astronomers are excited about this month’s eclipse because it coincides with the sun’s solar maximum. But many eclipse watchers don’t realize that much of what we know to expect this year is thanks to research done during the International Geophysical Year of 1957–1958.

Today, I offer a brief overview of some of the solar science advances made during the IGY, as playfully demonstrated on a few philatelic covers created for the occasion. Let’s start with a few definitions.

What is space weather?

Earth’s weather is dependent on the movements of particles (primarily water vapor) in our atmosphere. Winds and rains give way to storms and hurricanes. And while some types of weather can prove disastrous, the planet would be completely inhabitable without our protective atmosphere that spreads moisture and minerals around the globe.

Much as our planet has its own weather patterns, our sun generates “space weather” of its own. And that field of study has become more and more important as we place more and more objects into our upper atmosphere and beyond, all of which are vulnerable to the radiation emanating from the sun. According to the National Weather Service, space weather is divided into three categories based on its source and the effects it has on Earth:

- Geomagnetic storms are caused by coronal mass ejections (CMEs) and the high-speed wind from coronal holes. On Earth, these storms can create beautiful auroras, as well as cause problems for electrical systems, satellites, GPS, and radio systems.

- Solar radiation storms are associated with both solar flares and CMEs. These storms can be a danger to the health of astronauts and to people flying at high altitudes. They can also cause problems for satellites and radio systems.

- Radio blackouts are caused by solar flares, resulting in communications and GPS outages.

Solar flares, along with solar irradiance, sunspots, and other related phenomena, are highest when the sun is at its solar maximum.

What is the solar maximum?

Scientists have understood for hundreds of years that the sun has sunspots, and the frequency of those spots rises and falls at a predictable interval. The sun’s solar cycle lasts around 11 years, though it has been known to vary from 9–14 years. During this time, the sun goes through a period of “solar maximum” before dipping to a “solar minimum”, and at last returning to the “solar maximum” to complete one cycle.

During solar maximum, the sun generates a larger number of sunspots than average and the solar irradiance output (i.e. the amount of electromagnetic radiation) grows by about 0.07%. Large solar storms can develop when the sun is at maximum, raising the possibilities for solar storms.

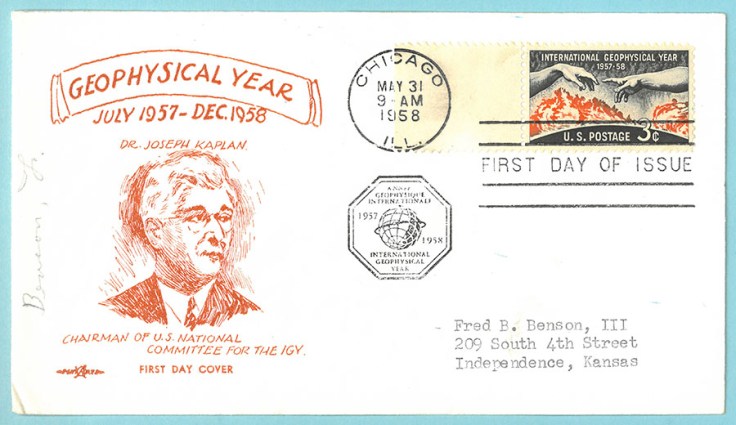

First Day Cover for the International Geophysical Year featuring Dr. Joseph Kaplan, the chairman of the U.S. National Committee for the IGY. The U.S. stamp features an image of the sun’s corona from a photograph taken during the first months of the IGY.

🇺🇸 United States, 3¢ | Issued May 31, 1958

What did we learn about the sun during the IGY?

The International Geophysical Year (IGY) was an 18-month international scientific effort directed to learn more about the processes of the Earth and our sun through 11 Earth sciences. (I’ve written a general intro to the event here.) The project ran officially from July 1, 1957–December 31, 1958, and included 10,000 scientists across 60 nations. Its timing was chosen in part to coincide with the peak of solar cycle 19, which would aid in many of the solar and atmospheric studies planned for the project. But even project organizers couldn’t have known that they were heading into a record-breaking solar maximum period that year.

IGY and solar observation

According to IGY: Year of Discovery, a book written by CSAGI President and IGY coordinator Sydney Chapman, “The study of the sun in association with the study of many earth phenomena was an essential feature of the IGY.”

Scientists were already long aware of the sun’s cycles, as well as the presence and occurrences of “sunspots, prominences, faculae, flares, and other visible kinds of changing activity on the sun’s surface—but with gaps in the period of observation.” This cooperative, global project was the first of its kind to study the sun continuously, even as the planet rotated individual research stations out of view. Specific attention was paid to studying the sun’s magnetic fields at several observation sites, as well as to its “great bursts of radio waves”.

IGY and sunspots

Our sun’s sunspot cycle has been observed and recorded continuously since the 1750s. However, as if it knew it was being watched and wanted to show off, the sun was never observed to be more active than it was during the IGY. Says Chapman:

In the first six months of the IGY, and especially in October 1957, the values of [the daily relative sunspot number] R rose beyond all those previously recorded during this long interval. Nevertheless the activity was shown by an abundance of small and moderate spots, and few great sunspot groups appeared, such as made records during the previous sunspot cycle (maximum in 1947). However, several great magnetic storms and auroras occurred during the year, indicating specially (sic) intense impulsion of clouds and streams of gas from the sun.

IGY, eclipses, and solar wind

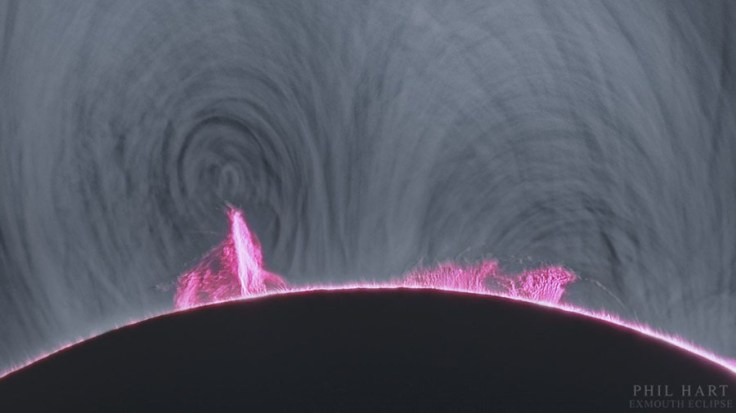

During the IGY, scientists increased their solar observations during several known solar eclipse days—even sending out expeditions to prime viewing locations. Why would you make a point to look at the sun while it’s being blocked by the moon? The sun’s brightness had historically made it difficult to study its features. During a solar eclipse, the body of the sun is blocked, making only its outermost layer, the corona, visible to observers.

Thanks to coronal observations made during the IGY, we now have a much better understanding of solar wind. According to the University of Chicago:

In 1957, [American astrophysicist] Eugene Parker … began looking into an open question in astrophysics: Are particles coming off of the sun? Such a phenomenon seemed unlikely; Earth’s atmosphere doesn’t flow out into space, and many experts presumed the same would be true for the sun. But scientists had noticed an odd phenomenon: The tails of comets, no matter which direction they traveled, always pointed away from the sun—almost as though something was blowing them away.

Today, we now know that, yes, the sun emits charged particles millions of miles into the solar system and that its solar wind helps protect our solar system from other harmful particles coming from space. We also understand how the solar wind creates auroras on Earth. And that strong storms from the sun can have damaging effects on our land-based and sky-based communications systems.

“The solar wind magnetically blankets the solar system, protecting life on Earth from even higher-energy particles coming from elsewhere in the galaxy,” explained UChicago astrophysicist Angela Olinto. “But it also affects the sophisticated satellite communications we have today. So understanding the precise structure and dynamics and evolution of the solar wind is crucial for civilization as a whole.”

IGY and the Van Allen belts

Thanks to the work of James A. Van Allen, the American physicist who designed the instruments on board Explorer 1—launched during the IGY—we also know about one more very significant feature of Earth related to the solar wind. Earth’s magnetic field regularly captures charged particles originating from the solar wind. These particles remain trapped in Earth’s magnetosphere, creating donut shaped bands now termed Van Allen radiation belts. These belts in turn shield Earth from the fastest, most energetic electrons originating from space.

So, Earth’s magnetosphere protects us from the worst of the sun’s solar wind, and that trapped solar wind in turn protects us from dangerous interstellar radiation!

First Day Cover for the International Geophysical Year featuring three stamps from Hungary’s set of seven demonstrating the various Earth sciences studied during the effort. The 1Ft stamp features an astronomical observatory and the sun, shown with sunspots and CMEs.

🇭🇺 Hungary, 10f–1Ft | Issued March 14, 1959

What can we expect to see during the eclipse on April 8, 2024?

Thanks in large part to the pioneering astronomy begun during the International Geophysical Year, we now have a much better understanding about what we can expect to see during this month’s solar eclipse.

According to Space.com, “On eclipse day [2024], 66 cameras fitted with special filters and distributed across three observing locations in Mexico and the U.S. will capture tens of thousands of images during the roughly four-minute eclipse.” The moon will act as a better occulter than any ground-based equipment ever could, blocking out the body of the sun and leaving visible only the sun’s outermost layer, the corona. As the source of solar wind, the photos taken during this eclipse have the potential to teach us new things about this “hidden” layer of the sun.

“Different types of ions emerge at different temperatures, so by imaging spectral lines of different types of ions, we can measure the temperature in different parts of the corona,” [Czech mathematician Miloslav] Druckmüller said. “That’s very difficult to do in other than the visible part of the spectrum and can’t really be done by probes in space, which don’t see the visible light.”

Perhaps what we learn will inspire another global scientific effort in the same vein as the International Geophysical Year!

What do you think? Do you plan to watch this month’s eclipse? How much do you know about space weather? Let me know your thoughts!

Leave a comment