Every year since 2017, my sister and I have taken a “sister trip” to one of America’s beautiful national parks. This spring, we visited a park in the Southeast that I’m sure many have never heard of, let alone visited: Congaree National Park.

Located right outside of Columbia, South Carolina, it’s hard to imagine a lush national park in the heart of this muggy maze of interstate roadways. And yet, Congaree’s swaying trees have stood for centuries—long before the sprawling development that thunders nearby.

The USPS has recognized many of America’s national parks and natural wonders on stamps over the last century. However, as a newer and smaller park site, Congaree has yet to receive that honor. But there is one seemingly unrelated stamp that helps tell part of Congaree’s story. Here are a few details about Congaree National Park and that stamp.

What is special about Congaree National Park?

Congaree National Park’s story is certainly one of resilience. The park bounds the northside of South Carolina’s Congaree River and encompasses just shy of 26,700 acres about 20 minutes southeast of the state capital of Columbia. That makes it the eighth smallest national park today. And it is also 12th from the bottom in terms of annual visitors. But I believe more people should visit this remarkable ecosystem and see its wonderful natural diversity for themselves.

According to the park’s handouts, “Congaree National Park protects the largest remaining tract of old-growth bottomland hardwood forest in North America.” That is to say, the forest is located on a floodplain (not a swamp)—which serves as the secret to its success, as well as its survival. “Waters from the Congaree and Wateree Rivers sweep through the floodplain, carrying nutrients and sediments that nourish and rejuvenate this ecosystem.” The result is one of the highest temperate deciduous forest canopies remaining in the world, averaging over 130 feet in height.

Congaree is known for towering loblolly pines, American beech, bald cypress, and water tupelos. Native tribes valued this wood for building canoes. Since colonization, there have been attempts to log the forest commercially, but fortunately, regular flooding made it difficult to do so economically.

Renewed logging in the late 1960s led to the 1972 formation of the Congaree Swamp National Preserve Association (CSNPA). Legislation was passed to create Congaree Swamp National Monument in 1976, much of which became a designated wilderness area in 1988 and an Important Bird Area in 2001. Congaree was officially established as a national park on November 10, 2003, dropping the misleading “swamp” from the name. Today, visitors enjoy self-guided boardwalk tours through the floodplain, as well as fishing and canoeing down the river.

What is the General Greene Tree?

Many of the hiking trails of Congaree National Park connect to the Harry Hampton Visitor Center in the northwest corner of the park. However, if you travel to the other end of the park, where Highway 601 crosses over the Congaree and Old Bates Rivers, you’ll find several parking pull-offs. The northernmost of these three marks one end of the Bates Ferry Trail (the other end of the trail terminates at the river).

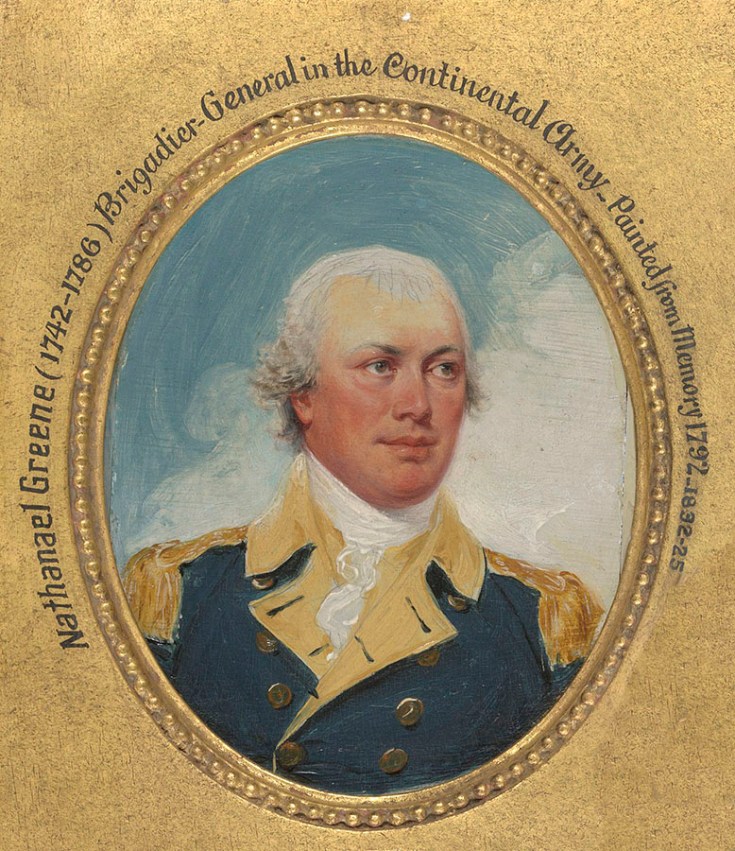

Head down this mile-long trail, and after about a third of a mile, you’ll see an unmarked spur trail leading to the right. Follow this path across a low steel bridge, and eventually you’ll come to an old-growth cypress tree with a ground-level circumference of 30 feet—the largest in the park! This tree is also unmarked, but park enthusiasts know it as the General Greene Tree. Named after Revolutionary War general Nathanael Greene, the tree is at least a few centuries old.

I wish I could post my own photo of the tree here. But Congaree flooded about a week before our recent visit, and when we crossed the bridge, all we found on the other side was water. However, according to Friends of Congaree Swamp, the remarkable tree survived logging (unlike two neighbors, whose stumps still stand to tell their tales) because it is hollow on the inside.

Who was Major-General Nathanael Greene?

Major-General Nathanael Greene (1742–June 19, 1786) served in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War and earned a reputation as one of George Washington’s most talented and dependable officers. In October 1780, Greene took command of the Southern theater of the conflict, successfully engaging in guerilla warfare against the more numerous British forces led by Lord Charles Cornwallis.

South Carolina history states that Greene met Brigadier General Francis Marion, “the Swamp Fox,” after the nearby six-day battle of Fort Motte not far from the tree that now bears his name.

Outnumbered and under-supplied, Greene’s strategy heavily depended on riverboats and cavalry to outmaneuver and harass British forces. The British took possession of Rebecca Motte’s Mount Joseph plantation, known as Fort Motte. They then seized control of nearby McCord’s Ferry on August 3, 1781. Greene ordered Lt. Col. Henry Lee “to strike at the enemy’s lines of communications from Orangeburgh to Charlestown,” which included the ferry point. Rebecca Motte, siding with the patriots, helped burn her own plantation to the ground by providing Greene’s army with lit arrows that were aimed at the dry wood roof. The British had no choice but to surrender, and 20 enemy soldiers were captured.

McCord’s Ferry was a privately run ferry service and a strategic river crossing point during the Revolutionary War. Well over a century before permanent bridges were in place across the Congaree River, these ferry points were integral to travel and access to supplies. The ferry remained in operation through the Civil War, during and after which it was known as Bates Ferry.

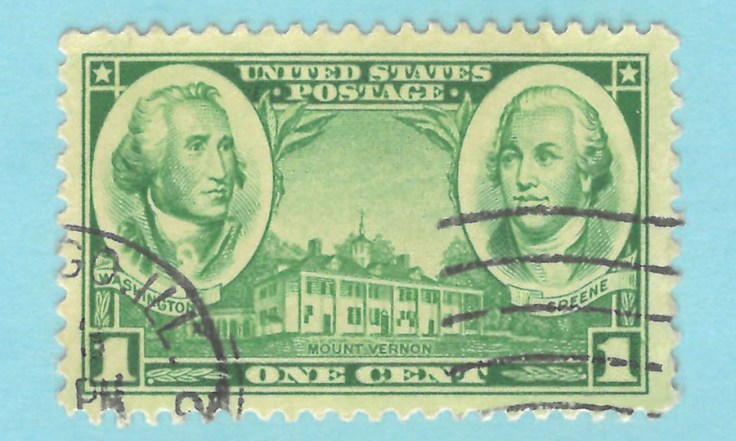

Army & Navy: George Washington, Nathanael Greene, and Mount Vernon

🇺🇸 United States, 1¢ | Issued December 15, 1936

When was Nathanael Greene featured on a stamp?

From 1936–1937, the post office issued ten stamps, ranging from one to five cents, known as the Army & Navy Issue. The stamps commemorated “famous military men, naval ships, residences of Army generals, and the military academies,” according to the Smithsonian National Postal Museum.

The first stamp in this series was a one-cent green stamp with George Washington’s residence at Mount Vernon as its central design. Portraits of Washington and Nathanael Greene inside oval cameos flank the image of the house. As one of Washington’s most valued generals, Greene was widely viewed as the “heir apparent” if Washington was killed or incapacitated in the war. His valuable service to the country was well remembered a century and a half later, at the time these stamps were issued.

Other stamps in the series include:

- 1-cent Navy – Jones & Barry

- 2-cent Army – Jackson & Scott

- 2-cent Navy – Decatur & MacDonough

- 3-cent Army – Sherman & Grant

- 3-cent Navy – Farragut & Porter

- 4-cent Army – Lee & Jackson

- 4-cent Navy – Sampson, Dewey & Schley

- 5-cent Army – West Point

- 5-cent Navy – Naval Academy Seal & Midshipmen

Since the 1930s, many stamps have been issued commemorating the Revolutionary War—particularly during the Bicentennial celebrations of the 1970s. However, barring another stamp issued in his honor, we will have to remember Major-General Greene’s patriotic service to our fledgling nation in other ways. Luckily, there are many statues and monuments erected in his honor. Multiple municipalities, 14 counties, and several ships have also been named after Major-General Greene.

What do you think? Do you like to visit national parks? Have you ever been to Congaree? Are you a Revolutionary War scholar with greater knowledge of McCord’s Ferry? Let me know your thoughts!

Leave a comment