🇭🇺 Hungary, 10f | Issued 1908–1913

Earlier this year, I purchased a small cover sent from Hungary with the express purpose of researching its postage due markings. At the time, I took little note of the cover’s recipient. But now that I have, I feel compelled to share what I have found!

Speculations about the addressee

It’s a proud fact in my family that a great uncle of mine worked at the Rochester Institute of Technology. When I realized that the addressee was the New York Institute of Science in Rochester, New York, I began to wonder: Could this be a previous name of the same institution? Had time and campus consolidation transformed the New York Institute of Science into RIT? That would give this cover special personal meaning!

As is becoming the norm with my philatelic research, a quick Google search showed me to be dead wrong. And pointed me in a completely unexpected direction.

What was the New York Institute of Science?

According to KookScience.com (here we go!):

The New York Institute of Science of Rochester, N.Y. was a mail-order company offering courses and degrees in the studies of personal magnetism, hypnosis, and occult science. It operated from 1899 until 1912, when the U.S. Post Office banned the mailing of its literature, effectively shuttering the organisation.

As the story goes, in June 1895, a stage hypnotist named Sylvain Lee performed for an audience at a business college in Sedalia, Missouri. One man in the audience, E. Virgil Neal (September 25, 1868–June 30, 1949), was a young business teacher. “The college instructors were so affected by the performance that they trained themselves as hypnotists, quit their jobs at the college, and at least one of them, Neal, went on tour. He and his wife Mollie performed as ‘X[enophon] Lamotte Sage’ and ‘Helen Olga Sage’.”

It seems likely that Neal and his colleague Sidney Abrams Weltmer saw dollar signs on stage during that hypnotism performance. The men “regarded the science and practice of hypnotism as a branch of persuasion, which, they believed, could be mastered through the development of ‘personal magnetism.’” Thus, hypnotism was a form of “salesmanship” which could be learned, enhanced through “personal magnetism” for personal gain, and ultimately, sold in turn for further profit.

Today, most of us recognize that as the very definition of a con man.

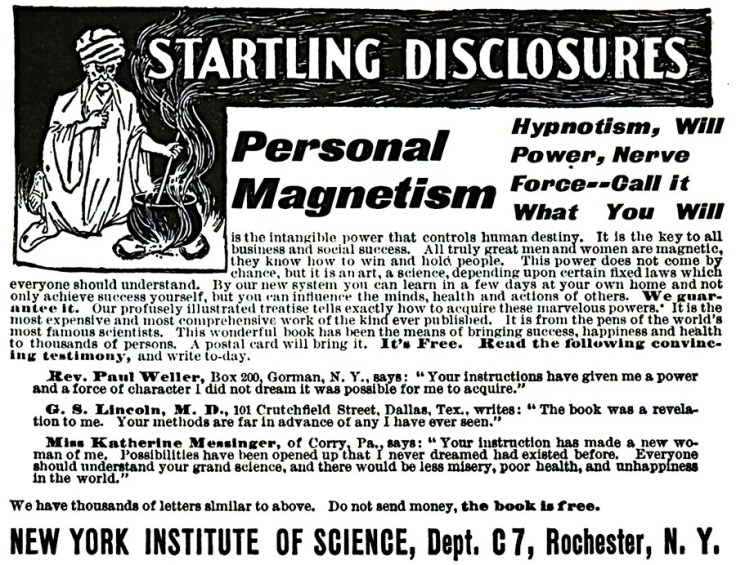

In 1899, Neal/Sage and a number of associates in Rochester formed the New York Institute of Science. The NYIS used a number of sales and marketing techniques, including full-page newspaper ads, to offer a variety of home-study courses on magnetic influence and hypnotic power. The courses claimed to “enable one to cure disease and bad habits without drugs, win the friendship and love of others, increase one’s income, gratify one’s ambitions, dispel worry and trouble from your mind, banish domestic unhappiness, end pain and suffering and develop a wonderful magnetic will-power that would enable one to overcome all obstacles to one’s success.”

Convincing stuff.

What happened to the New York Institute of Science?

Through the international mail system, Neal/Sage and his colleagues at the NYIS aimed to propagate their schemes throughout the world. (In fact, Neal quietly transferred leadership of the institute after just a few years, but the NYIS kept advertising “Dr. X. LaMotte Sage” as the active president.)

The NYIS made extensive use of mailed advertisements, taking full advantage of U.S. printed matter rates (1¢ per 2 oz. of weight, about 56 grams). They would offer recipients a free introductory booklet, and then upsell them a home-study course. The cost of the course booklet was about $5 U.S., which is the equivalent of more than $100 today. Upon receiving the first course booklet, customers would discover an additional 40 compelling courses available—for purchase, of course.

Of course, there’s nothing illegal about just mailing customers literature about hypnotism. However, the NYIS did not stop there. They also peddled dubious mining stock, real estate schemes, and—perhaps most easy to prosecute—worthless patent medicines, such as “Nuxated Iron” and “cartilage stretchers”.

By 1912, the Attorney General of the State of New York, the U.S. Postal Service, and the American Medical Association had received enough complaints of fraud against the NYIS to pursue legal action. Court proceedings against the NYIS were held from November 17–20, 1913. By late the next year, the Assistant Attorney General of the State of New

York issued, in part, the following statement:

For years the Department has been flooded with complaints against this concern (the NYIS) from people claiming to have been defrauded and it is estimated that this concern has mulcted the public to the extent of $1,500,000 (equivalent to $47,600,000 in today’s dollars). I find that this is a scheme for obtaining money through the mails by means of false and fraudulent pretenses, representations and promises in violation of Sections 3929 and 4041 of the Revised Statutes, as amended, and I therefore recommend that a fraud order be issued against the New York Institute of Science, Inc., and its officers and agents as such.

The Postmaster General issued the fraud order on August 8, 1914. By the end of the year, the NYIS had ceased activities.

What happened to X. Lamotte Sage?

Neal/Sage left NYIS in 1902, though his purported involvement did earn him charges during the court proceedings in 1913. But by then, he had started nearly a dozen other ventures of various degrees of dubiousness, including courses in Vitaopathy (psychic healing), lecithin supplements, and methods for bust development.

In 1907, Neal founded the To-Kalon (or Tokalon) Manufacturing Company, which manufactured cosmetics, soaps, and perfumes. He would build that into one of the most successful cosmetics companies in Europe. Neal would be the subject of a Time magazine article in 1933, recipient of the cravat/necklet of Commander of the Crown of Italy, and was made a French Officer of the Legion of Honour. He lived his later years in Nice, France, and became one of that city’s most prominent citizens.

However, Neal continued his brushes with controversy. In June 1919, he was the subject of a $100,000 libel suit in the U.S. over his widely advertised patent medicine concoction “Nuxated Iron.” There is also evidence that Neal continued to market a version of his hypnotism course in Europe as late as the 1920s. Still using the name of X. La Motte Sage for its marketing, the price for the course soared to $25 U.S. or 5 Guineas in British currency!

What can we learn from the NYIS?

The early years of the 20th century saw no shortage of pushy salesmen, fraudsters, worthless patent medicines, and public fascination with astrology, numerology, palmistry, and other dubious “sciences”. In fact, prolific nostrums like “Nuxated Iron” led to the establishment of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which was created to prevent the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of adulterated or misbranded or poisonous or deleterious food, drugs, medications, and liquors”.

More than a century later, the American public is still grappling with persuasive marketers of unproved miracle cures—this time in the form of cable news pundits and social media influencers. Bad products abound, from counterfeit goods to unregulated “legal steroids”. A burgeoning “wellness” industry touts miracle cures for minor cosmetic differences, from Goop’s infamous jade yoni eggs to herbal weight loss supplements labeled “nature’s Ozempic”.

And the “science of salesmanship” continues unabated, as well. Influencer marketing is worth more than $21 billion globally. More than that, “financial geniuses” continue to push MLM schemes, savings “hacks”, and get-rich-quick hustles. “Hustle culture” has been on a high for years.

President Theodore Roosevelt may have taken a big bite out of the consumer fraud market more than a century ago. But the NYIS reminds us that there are still plenty of consumers eager to “cure disease and bad habits without drugs, win the friendship and love of others, increase one’s income, gratify one’s ambitions, dispel worry and trouble from your mind, banish domestic unhappiness, end pain and suffering, and develop a wonderful magnetic will-power”. And with the proliferation of internet commerce, there are more opportunities than ever to defraud them in pursuit of their goals. But now that fraudulent businesses are no longer obtaining money directly through the mail, we must find newly effective ways to protect modern consumers.

What do you think? Are you familiar with other companies that trafficked in mail-order occultism? Do you think product fraud is still a danger to consumers? Let me know your thoughts!

Leave a comment