🇬🇧 Great Britain, 24p | Issued February 16, 1993 | SG GB 1654

Since 2020, many people (myself included) have felt that time isn’t what it used to be. Days are too long and too short at the same time. Hours take weeks. Months go by in a flash.

We forget that centuries ago, humankind’s relationship to time was fundamentally different. Workdays were measured in sunlight. Years were measured by the seasons. And there were no precise 4:15 pm movie matinees to rush into before the credits began (or ended—your choice). But step by step, we began to fine tune our relationship to time. Timepieces became a way of not only reflecting, well, time, but distance and status and even the excitation of atoms.

Our new relationship to time can be traced back to several innovators of precision engineering. But arguably, the first to open up the world of horology was John Harrison, commemorated by this stamp of Great Britain.

What’s on the stamp?

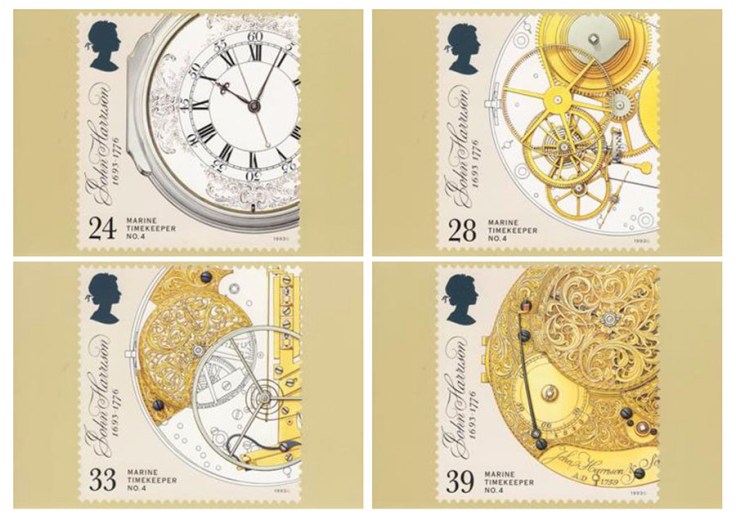

We know this is a British stamp because of Queen Elizabeth II’s silhouette in the top left corner. Along the left side in a beautiful calligraphic font are the words “John Harrison 1693–1776” turned 90 degrees counterclockwise. In the bottom left corner is the denomination, 24 (pence), and the words “Marine Timekeeper No. 4”.

But the bulk of this square stamp’s image (I’d say 80%) is taken up by a portable timepiece that is so large on the stamp it runs off the frame on the top and right. This clock face, with a hinge on the left, shows the hours in bold Roman numerals and the minutes in increments of five. Around the ring of numbers are flourishes of incredible intricacy and delicacy. But the precision of these flourishes only hints at the level of precision found within.

What else was featured in the set, and what did it commemorate?

This stamp was just the first of four issued by Great Britain in 1993 to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the birth of English clockmaker John Harrison. The other three show various layers of precise cogs and wheels inside the H4 timepiece. In order, the stamps feature:

- Decorated Enamel Dial, 24p.

- Escapement, Remontoire, and Fusee, 28p.

- Balance, Spring, and Temperature Compensator, 33p.

- Back of Movement, 39p.

According to Collect GB Stamps, these stamps were issued alongside a lovely presentation pack that tells the history of Harrison’s revolutionary invention. There was also a stunning first day cover with a cache featuring Harrison and the ship that carried the timepiece. As well as several versions of a poster from the Royal Mail announcing their release date.

Who was John Harrison, and why was he important?

John Harrison (March 24, 1693–March 24, 1776) was a Yorkshire carpenter and joiner who became the most acclaimed clockmaker of the century—perhaps of all time. Harrison engineered a series of painstakingly constructed and unimaginably precise clocks that were better than any constructed by humanity to that point. In so doing, he solved “the longitude problem” and rightfully won the rights to a £20,000 prize issued more than 40 years previously.

For millennia, travelers on land and sea understood how to precisely pinpoint their latitude. But by sea, the only way to know your longitude was by comparing the time at one stable (i.e. land) reference point and another reference point on the globe. Without accurate timekeepers, ships could not determine their precise location and were more likely to become lost or veer off course. But the best timekeepers of the early 18th century were large, pendulum-driven clocks that lost their accuracy while rolling on the high waves of the choppy sea.

Harrison understood that a portable precision clock could not be pendulum driven. Over the course of four prototypes (and nearly 31 years), he created incrementally more effective designs: H1, H2, H3, and H4. The last design, the H4, squeezed all of his improvements into a five-inch silver case. The result was the first marine chronometer, a portable clock that kept precise time, even when at sea, and the precursor of the pocket watches of the 19th century and wristwatches of the 20th.

(Notably, the H4’s successor, the K1, was the device Captain James Cook took with him on all his voyages.)

In addition to saving countless sailors from colliding with sandy shoals and rocky islands, the marine chronometer had a vital economic value. More precise navigation meant trading routes could be more quickly traveled—and more heavily policed. The invention no doubt helped Great Britain become master of the world’s oceans.

Want to learn more about John Harrison?

The level of precision Harrison achieved in his H4 set a new standard for technology and measuring time. My oversimplification of the longitude problem and Harrison’s ingenious solution does a disservice to the man’s lifeswork.

If you would like to read more about Harrison’s achievement, I recommend The Perfectionists by my favorite author, Simon Winchester. The Perfectionists outlines the history of precision engineering from the dawn of the Industrial Revolution to technologies on the horizon today. It’s a fascinating book for anyone who would like to learn more about how the world as we know it was engineered through a series of ever-more-precise innovations, from cannon barrels to space telescopes.

I also highly recommend the 1995 best seller Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time by Dava Sobel. It’s been a few years since I read that one, but it’s one of the few books I regret sharing because now I no longer have a copy on my shelf.

What do you think? Was this the first you’d heard of John Harrison, or is he a household name where you live? Do you collect stamps related to timekeeping or seafaring? Let me know your thoughts!

Great read! It would be easy to dismiss this stamp as just a pretty picture of an antique, but you brought to life the fascinating story behind it. I want to know more about Mr Harrison now!

LikeLike

Thank you! I didn’t even get into the scandal about the prize money. He’s definitely worth learning more about.

LikeLiked by 1 person