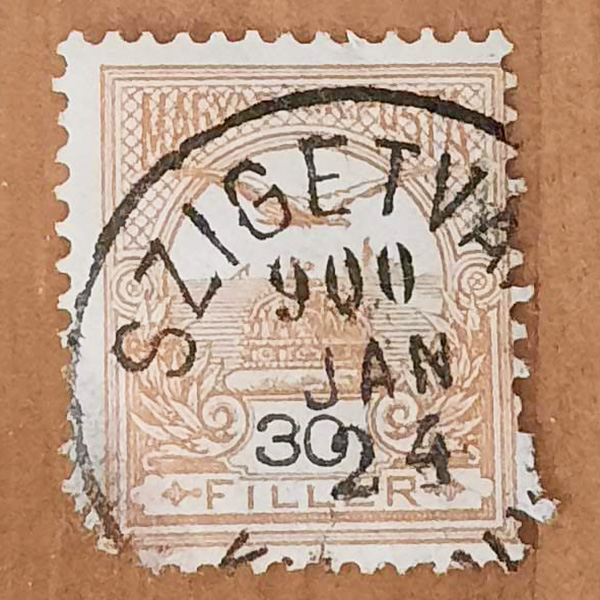

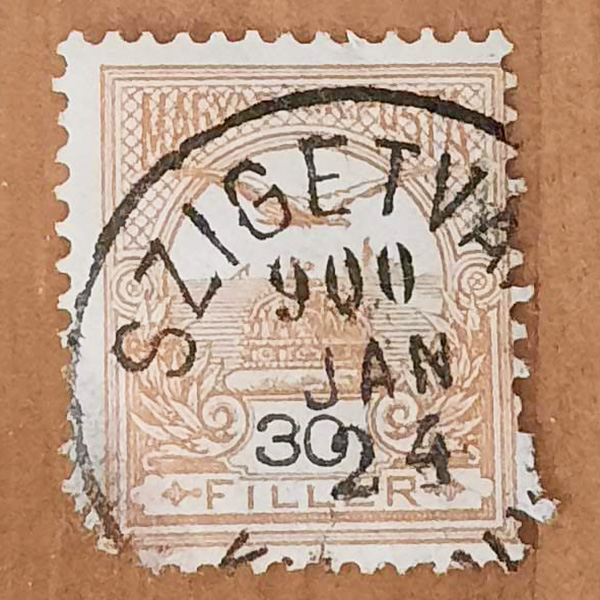

🇭🇺 Hungary, 30f | Issued January 1, 1900 | SG 75

Okay, let’s get right to it. Did this particular stamp single-handedly save Western civilization? Absolutely not. … Probably.

But it was canceled at a spot that did. At least, according to the villain of The Three Musketeers.

You never know what interesting history you’ll uncover when you look more closely at a postage stamp. Here’s a quick rundown of the Hungarian town of Szigetvár and an intense 16th century battle of the same name.

Where is Szigetvár?

Szigetvár is a small town in southern Hungary’s Baranya County. The name is a compound word meaning “Island Castle”, for reasons we’ll see below. Baranya County borders Croatia to its south. The town is just a short drive to Pécs, the largest city in the county.

Before the nation of Hungary was established, the area was populated by Slavs and Avars. Over the centuries, the borders of Hungary have waxed and waned. Today, “Baranya has the largest number of minorities in Hungary (more than twice the country average)”. Ethnic Hungarians still make up more than 86% of the population, but there are also many Germans, Bulgarians, Romani, Croats, and Serbs. Religious populations are equally mixed, and there are a number of prominent churches and mosques in Szigetvár.

Today, Szigetvár has a population of around 12,000 people. The local economy is buoyed by production companies and tourism. One large company, Trust Hungary Zrt., produces Hungarian and American oak wine barrels. There is also a large locksmith metalworks in town. Tourist attractions include Hungary’s first cornhusk museum, a “mermaid” pond, a thermal spa, and the Hungarian-Turkish Friendship Park (more on that below).

What happened at the Siege of Szigetvár?

The origins of Szigetvár

Historians estimate that the first bricks of the fortress of Sziget were probably laid around 1420 on a hill named Lázár Island in the marshland of the Almás River. Over several decades, brick buildings were erected—followed by a stone tower, ramparts, and moats—to create a citadel on an island. It was quickly followed by a castrum (castle) and small town. Drawbridges connected inner and outer citadels, and the moats effectively created an artificial lake around the community. Thus, Szigetvár, or Castle Island, was born.

The battle on Szigetvár begins

The origins of the citadel’s month-long siege began in 1526, when the independent Kingdom of Hungary fell in the Battle of Mohács and Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I was elected king by the nobles of Hungary and Croatia. Those actions resulted in a series of conflicts between the Habsburg monarchy and the Ottoman Empire, led by Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.

In May 1566, at 72 years of age, Suleiman decided to advance towards Vienna. He left Constantinople at the head of a massive army in his thirteenth military campaign. But Suleiman, and tens of thousands of his soldiers, would not return home.

Count Nikola IV Zrinski, Ban (royal representative) of Croatia, led troops fighting for the Habsburgs. Zrinski successfully attacked a Turkish encampment at Siklós, leading Suleiman to reroute his troops to eliminate the encroaching threat. Suleiman arrived at Szigetvár on August 5, 1566. The Ottoman forces, led by Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha and numbering 150,000, surrounded Zrinski’s force of around 2,300 Croatian and Hungarian soldiers, trapping them. They greeted the Ottomans by draping the fortress walls with red cloth, as though for a festive reception.

As Wikipedia succinctly recounts it,

Szigetvár was divided by water into three sections: the old town, the new town, and the castle—each of which was linked to the next by bridges and to the land by causeways. … Despite being undermanned, and greatly outnumbered, the defenders were sent no reinforcements from Vienna by the imperial army. After over a month of exhausting and bloody struggle, the few remaining defenders retreated into the old town for their last stand.

The Hungarian forces continued to fight, even as Suleiman died of natural causes in his tent on September 6. His death was kept a secret for 48 hours to prevent the demoralization of the Ottoman troops.

The final attack on Szigetvár

The Ottomans, led by Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, completed an all-out final attack on Szigetvár on September 7. The fortress walls had finally fallen due to mining, explosives, and “relentless cannonading”. The Ottomans used “Greek fire” and more than 10,000 large cannonballs to take the castle. Even as the Ottoman army charged through the city, Zrinski stood by his men, leading the remaining 600 out of the castle to defend their homeland.

He was famously known to have addressed his troops, saying:

Let us go out from this burning place into the open and stand up to our enemies. Who dies: he will be with God. Who dies not: his name will be honored. I will go first, and what I do, you do. And God is my witness—I will never leave you, my brothers and knights!

Unfortunately Zrinski’s enthusiasm was no match for the Ottomans’ fire. He was shot twice in the chest by muskets, and was finally killed by an arrow to the head.

Even without their leader, the Hungarian and Croatian troops continued to fight. As Ottoman raiders entered what was left of Szigetvár in search of the castle’s rumored treasure, they fell into Zrinski’s pre-laid booby trap. Thousands died instantly from a huge explosion of the castle’s 3,000-pound powder magazine.

Only seven of the citadel’s defenders managed to escape through the Ottoman lines. A few other captured defenders were spared by Ottoman leaders who admired their courage. But by and large, the 34-day siege wiped out nearly all of Zrinski’s 2,300 soldiers. However, the Ottomans lost ten times as many men in the conflict, along with their sultan. Sources estimate 20,000–35,000 men died in the battle. Though the Ottomans had decisively won, the question remains: at what cost?

How did the Siege of Szigetvár save Western civilization?

Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian sent two ambassadors to Istanbul shortly after the siege, in 1567. By February 1568, the Austrian and Ottoman empires reached an agreement to end the war. The Treaty of Adrianople, signed on February 21, 1568, established an eight-year truce. In reality, the agreement brought about 25 years of (relative) peace between the empires.

Almost immediately, the battle came to symbolize nationalism in the face of invading forces. So important was the battle in pushing the Turks out of Europe—for more than a century, no less—that French clergyman and statesman Cardinal Richelieu is believed to have described it as “the battle that saved (Western) civilization”.

Though the Szigetvár fortress suffered significant damage, it would later be repaired and even strengthened with brick and stone walls. Szigetvár remained under Ottoman control until 1689. The citadel retained its military role until the end of the 18th century. The internal organs of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent were entombed in the nearby destroyed settlement of Turbék. Recent archaeological digs are revealing new details about the tomb.

The Battle of Szigetvár inspired epic poems in Croatian and Hungarian—the latter, “The Peril of Sziget”, written by Zrínyi’s great-grandson, Miklós Zrínyi. The heroic actions of the citadel’s defenders against the Turks also inspired a German drama and Croatian opera. The battle continues to inspire many political movements in modern times.

In 1966, on the 400th anniversary of the siege, Szigetvár received city status in Hungary. In 1994, Hungarian and Turkish officials jointly dedicated the nearby Hungarian-Turkish Friendship Park, a one-acre public park memorializing the Battle of Szigetvár. In the park, monuments depicting Count Zrínyi and Sultan Suleiman stand side by side.

What else can we learn from this stamp?

As I’ve written before, the mythical Turul bird is the Hungarian national symbol of god’s power and will. It is no coincidence that the Turul was prominently featured on many early Hungarian stamps, including this series which ran from 1900–1916.

According to “Postage Stamps of Hungary” by Tony Clayton, the Turul bird issue was initially released on January 1, 1900 to coincide with a change in currency. A set of lower values (in filler) featured the mythical bird flying over the crown of Hungary, while the higher values (in korona) featured a profile of King Francis Joseph. Several reprints with different watermarks and perforations were issued over the next several years. But with a clear cancellation of January 24, 1900, we know this stamp was of the first variety.

It is perhaps also serendipitous that this Turul stamp was canceled in Szigetvár, itself now a symbol of Hungarian strength in the face of adversity. This hand stamp design, well centered on the stamp, was not uncommon for its time. We see the town name along the top of the single circle. In the middle is a three-digit year (new as of 1900), an abbreviation for the month, and a numeral for the day. However, without knowing what appears on the bottom line, we can’t determine anything more about the hand stamp, such as whether it was bilingual (possible, considering the proximity to the Croatian border) or if it featured the castle county name or regional description.

What was happening in Szigetvár in 1900?

At the turn of the 20th century, Szigetvár was a quiet town finally coming into its own as a location for industry and opportunity.

According to Hungarian Wikipedia, the Pécs–Barcs railway, put into service in 1868, finally connected Szigetvár to the national transportation network, opening up opportunities for large industrial investments. A steam mill opened in 1881, followed by a shoe factory in 1884 that would become a significant part of the city’s modern history.

The town was not the only Szigetvár making waves in 1900. SMS Szigetvár was a 320-foot protected cruiser of the Zenta class built for the Austro-Hungarian Navy. Along with two sister vessels, Szigetvár was the first major warship of the Austro-Hungarian fleet to be armed entirely with domestically produced guns.

Szigetvár was laid down at the Pola Arsenal on May 25, 1899. Christened in honor of the siege, she would launch on October 29, 1900. Over her 20 years in service, Szigetvár would cruise to North America and northern Europe before serving in the main Austro-Hungarian fleet for most of World War I. She would be ceded to Britain as a war prize and was scrapped in 1920.

What do you think? Were you aware of this important battle? Do you collect stamps related to European battles or the Ottoman Empire? Let me know your thoughts!

A very interesting article, it encouraged me to take a closer look at the cancellations on some of my collection’s stamps!

LikeLike

Thank you for a very interesting article about a cancellation on a classic postage stamp !

LikeLike